With Uber’s listing and our view this kicks off Silicon Valley’s endgame, we travelled to the Bay Area to conduct more on-the-ground research. We met with over 100 founders, angels, VCs, allocators, and hedge funds. In this report, we share some of the key insights from our trip. It is surprising to us why more people are not looking in and connecting the dots.

1. While there have been a lot of interesting innovations in this cycle, the real differentiator has been the access to capital—in both scale and speed. An app connecting supply with demand is no longer a novel concept. But as Naval Ravikant put it, “The dirty secret of the tech business is that network effects create natural monopolies and oligopolies. The number two platform often isn’t viable.” Hence, most tech companies choose growth over profit and operate with exceptionally high burn rates, which requires a steady flow of capital. A focus on making money would entail sacrificing too much market share. The idea is to spend aggressively to get users hooked on a service by bringing it to market at a price point that is highly attractive—and beat the competition. Uber is a textbook example of this.

But as companies mature, money pumped to keep scaling up turns out to be less efficient and burn rates become unsustainable. Customers pay back the cost of acquisition more slowly and negative gross margins start to strain the business. As growth is the mantra everyone agrees that’s still okay and it can be fixed later. But as the company scales further or once it goes public, the problem becomes more evident. Taking prices up or driving costs down without impacting growth, in order to get to positive gross margins is a lot harder than most people think.

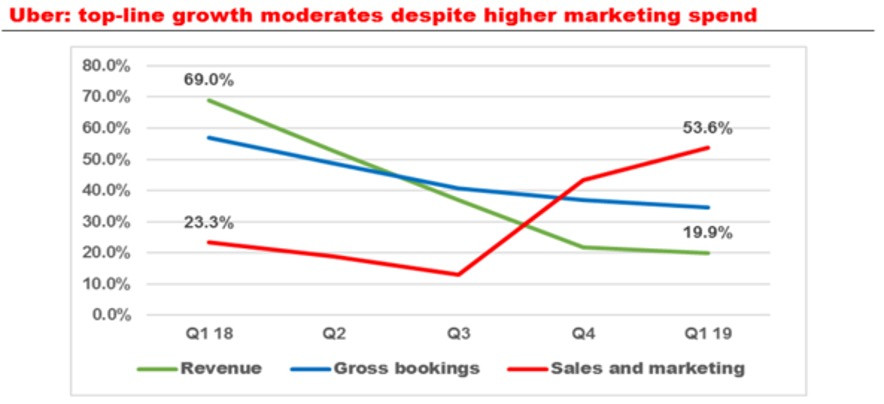

Uber said that it burned through $851 million in cash from operations and capital expenditures in the first quarter, more than double the amount it burned in the same quarter a year ago. At the same time, revenue rose by just 20% during this period, even though Uber spent 54% more on sales and marketing. For Uber’s food delivery business, Uber Eats, the company had to triple “excess driver incentives,” an increase of nearly $200 million, to grow revenue by $253 million.

Source: Uber, RedEx Research

Most on-demand companies were created after the 2008 financial crisis when jobless rates were high and finding people to drive was easy. Now the unemployment rate is at a 50-year low and it requires more money to sign up more drivers. At the same time, minimum wages are rising, drivers are striking, and most on-demand companies are still losing money, using investor cash to subsidize their services. It is unclear how Uber plans to eventually get to its long-term 25% EBITDA margin target, compared to actually a negative margin of 34% in the first quarter.

To quote Fred Wilson of Union Square Ventures, “Most of the companies using a negative gross margin strategy are going to find that the capital markets will ultimately lose patience with this strategy and force them to get to positive gross margins, which will, in turn, cut into growth, and what we will be left with is a ton of flatlined zero gross margin businesses carrying billion dollar plus valuations.”

2. The conventional wisdom in Silicon Valley is that when building the very best companies, more capital can be leveraged to accelerate even greater growth. But we noticed an unsettling trend of what can only be called the “financialization of founders.” Some founders complained they were being compelled by their board and investors to raise more money than is actually required, forcing them to prematurely scale and get into an “arms race” with their competitors. Founders commit to aggressive milestones as a result, which they are not confident of achieving. They admitted feeling great pressure to perform.

This toxic overexposure to capital counterintuitively makes companies more fragile, masking a death spiral if there’s a down round. It is entirely possible for a good entrepreneur with a great business idea and a long-term path to profitability to lose his company if an economic downturn sets in and investors pull the plug. According to Eric Paley, a Partner at Founder Collective, “VC kills more startups than slow customer adoption, technical debt and co-founder infighting combined.” It felt to us like founder and VC incentives are no longer as aligned as they once were, with the latter more return-oriented than mission-oriented now.

3. What is driving this “financialization” is that there are more investors than operators in Silicon Valley. Most people who have had successful exits don’t want expensive homes or cars; what they want is the next unicorn. Their first instinct is to sprinkle money on other founders. As Sam Altman said, “Seed investing is the status symbol of Silicon Valley.”

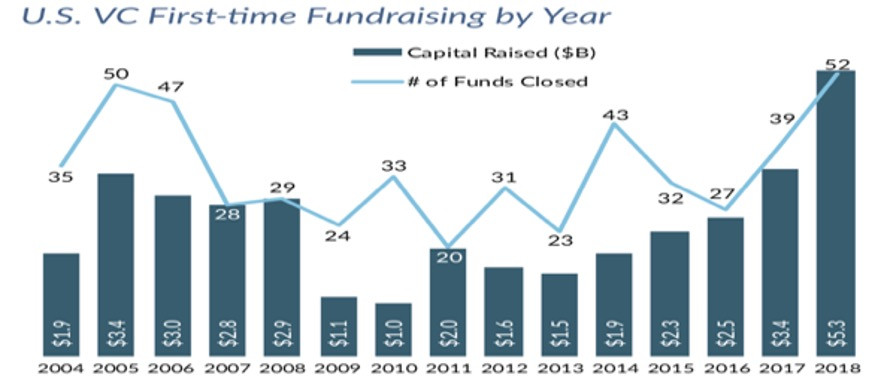

With so many new people and funds in the market looking to put capital to work, the velocity of money in the ecosystem is speeding up with faster deal making to show LPs. It’s no surprise that this is driving up median deal sizes at every stage. In 2018, 52 first-time raised over $5 billion, a 15-year high, at perhaps the least propitious time in VC history to start.

Seed funds are investing in fewer startups for more equity, which means getting in attractive deals has now turned into a “blood sport,” as we were told by one investor who specializes in seed-stage investing and was an early investor in Uber. “It used to be a lot more collaborative a few years ago.” VCs have raised larger funds that allow them to pay higher prices in later rounds and still hit preferred ownership sizes. Growth- and late-stage funding is exploding. Sequoia Capital’s Global Growth Fund held an $8 billion final close in September, making it the largest VC fund closed to date.

Source: Pitchbook

4. Silicon Valley employees working for large companies like Google and Facebook were happy and excited about their jobs in 2012—but now feel jaded and disillusioned by the simmering “techlash,” the sharp rebukes of big tech companies with growing calls for regulation and crackdowns on monopolistic practices. There is growing unease about the impact these companies are having on everyday life with the proliferation of fake news, social media addiction, concerns over data pricy, and the polarization of communities. Many employees no longer feel pride in what they do, but they earn such extravagant packages that it is not economically viable for them to leave. It happens that in most instances the peers that left to do their own thing would have been better off just staying and holding onto their stock. Stock for Google-parent Alphabet has quadrupled over the past seven years, Facebook’s stock has risen eightfold. The corollary is Silicon Valley’s risk-taking culture is waning and startups face a significant talent crunch as hiring becomes more difficult.

5. A commonly held view is that Silicon Valley has a unique DNA and that it will always be the center for American and global innovation. As one investor said, “We get some of the best of the best and they all want to be in that place. Cyber Mecca!” But the truth is there is an exodus from Silicon Valley. We heard many reports that more and more teachers, nurses, and doctors are leaving because the cost of living is too high. One founder who sits on the board of his child’s school said that “teachers leaving is a big problem.” Stanford is working to expand housing options for faculty and staff members to live in close proximity to the main campus. A median-priced home in the San Francisco Bay Area costs $940,000—more than four times the national average. According to a recent survey, 41% of 18- to 34-year-old tech employees plan to leave the Bay Area in the next year.

In the 1970s, the chip industry was emerging, and Intel built the first microprocessor in San Jose. Later the center shifted closer to Stanford as smaller and faster computers with more computational ability were built and the use spread. The rise of the Internet in the 1990ss encouraged graduates to build Internet-related companies like Google. It was easier to locate around Menlo Park and Palo Alto as they were funded by university professors and could easily recruit from the campus.

The transition from the peninsula to cities began around 2012, when smartphones became ubiquitous and the mobile app revolution took off. It no longer made sense to cluster around the university—it was better to be based in the city to find solutions to everyday problems. Consumer-internet businesses like Uber and Airbnb were formed, as well as rival tech hubs in other American cities like Boston, New York, and Austin. Investors put half of their money into startups outside the Bay Area five years ago; now it is closer to two-thirds. We see real estate continuing to perform well in these newer tech hubs as the exodus from Silicon Valley accelerates. One founder who just came back from Austin agreed. “People there think the market is pretty crazy right now. But the boom has a long way to go.”

It is estimated that more than 5 billion people have mobile devices today, and over half of these connections are smartphones. So where will the next Silicon Valley be? “It will just sort of be everywhere,” said Sam Altman. The implementation of the next generation of ideas does not need to be Silicon Valley-centric or even US-centric. The US received 95% of global venture money in the mid-1990s. It’s now down to half. Startup activity and investment are concentrating in some of the world’s largest mega-cities.

6. Unfortunately, the San Francisco homelessness crisis is very real—and no one we met has any real solution to the problem. Walking through the Tenderloin neighborhood was particularly jarring, seeing people shooting up as we walked on by. One founder and angel investor in PayPal and Airbnb told us, “It’s so shit out there that we just prefer to stay in our offices and work all the time.” The views from the office towers are truly breathless—a sharp contrast to city streets strewn with trash, syringe caps, and homeless campers.

Silicon Valley is highly uneven. On-demand companies have classified the legions of workers they rely on as independent contractors to keep their costs low. But gig workers, with no benefits or security, are now fighting to be classified as employees. More than 36% of American workers—57 million people—belong to the gig economy, according to Gallup, and 29% of workers are doing gig work as their main job. The gig economy has grown quickly over the past few years, bringing in as much as $864 billion annually, according to some estimates.

Less than a month after Uber drivers went on strike to protest low wages and their status as contractors, California has passed legislation requiring on-demand companies to recognize much of their workforce as employees entitled to labor protections and benefits such as minimum wage, overtime pay, and protections under antidiscrimination laws. The bill was approved 53 to 11 and now moves to the state Senate. If signed into law, this could have a profound effect on their business models, and the way lawmakers around the country think about addressing tech workers’ rights. The Labor Department still classifies gig workers as contractors, not employees.

7. The corporate leadership pendulum has swung from one extreme to another. In 1972, Don Valentine founded venture capital firm Sequoia and backed successes like Apple, Cisco, and Oracle. He famously said, “I am 100% behind my CEOs right up till the day I fire them.” Sequoia put $2.6 million in Cisco in 1987 for 30% of the company. Don almost immediately appointed John Morgridge as the new CEO and ousted founder Sandy Lerner. “The first time I met John he had already been hired,” Lerner later recalled. That was a time when the board reigned supreme.

Today, founders of successful technology startups are omnipotent and have all the power. Big tech companies including Google, Facebook, and Snap have supervoting structures that give their founders control. In Snap’s case, the company sold shares to the public with no voting rights; the founders control about 90% of its voting power. The founders of Lyft also took near-majority voting control despite together owning a stake of less than 10%. WeWork founder Adam Neumann took control of 65% of voting equity as part of a 2014 funding deal.

Facebook’s Class B shares, controlled by Mark Zuckerberg and a small group of insiders, has about 18% of the shares, but they also have 10 votes per share. That gives him 57% of the voting power, which makes it near impossible for shareholders to force change in the way the social media company manages itself, or even force change in management. It is hard to hold Zuckerberg accountable for the company’s privacy scandals. It’s a different world we live in today with the power concentrated in one person. Benchmark general partner Bill Gurley said Silicon Valley board rooms have mostly become people applauding founders and giving them a lot of leeway. Facebook shareholders voted down a proposal that sought to split the chairman and CEO roles that Zuckerberg holds and establish an independent board leader.

But we think this is going to change once a technology bear market gets underway. Dual voting-class shares have been controversial for years and the structures have started to get pushback from governance experts. Last year, the Council of Institutional Investors recommended multiple class listings should be removed from equity indexes.

8. The big story was Uber’s IPO. In its investor roadshow, Uber CEO Dara Khosrowshahi likened the ride-hailing company to Amazon. “Cars are to us what books are to Amazon. Amazon was able to build this extraordinary infrastructure on the back of books and go into additional categories, you are going to see the same from Uber. We want to be the Amazon for transportation.”

Following a disappointing flotation, Dara reminded employees, “Amazon’s post-IPO trading was difficult as well but look at how they have delivered since… Uber has all the capital we need to demonstrate a path to improved margins and profits.” The thing is Amazon went public after three years at a market value of $438 million. Uber is 10 years old and was valued at $82.4 billion on its IPO.

We did not come across anyone who wanted to buy Uber’s stock, except our friend and Uber driver Xinyi. She said Uber offered her to buy shares at the IPO price. She now sits nervously on a 12% loss. A whopping 81% of the $29.5 billion in equity that Uber has raised is underwater.

Amazon has returned about 100,000% since its 1997 IPO. Uber delivered stronger gains for some of its earliest investors. A $10,000 investment at seed is currently worth about $30 million. But it is hard to see Uber’s stock do as well in the public domain. Amazon went public with revenues of $16 million and a loss of $3 million. Cumulative net losses over its first nine years totaled $3 billion before it turned profitable in year 10. Uber lost $3.7 billion in the 12 months through March and $10 billion since its founding in 2009, the most ever for a company to go public. We suspect Uber will continue to lose money for several years to come.

9. In Wall Street, it was the lack of discipline on leverage rules and the dismissal of risk frameworks that led to the subprime meltdown. In Silicon Valley today, it is the lack of capital discipline and dismissal of economic realities which will lead to a phenomenal tech bust.

This warning from Bill Gurley looms large: “The very act of dumping hundreds of millions of dollars into an immature private company can have perverse effects on a company’s operating discipline. Companies are taking on huge burn rates to justify spending the capital they are raising in these enormous financings, putting their long-term viability in jeopardy. Late-stage investors, desperately afraid of missing out on acquiring shareholding positions in possible “unicorn” companies, have essentially abandoned their traditional risk analysis. Traditional early-stage investors, institutional public investors, and anyone with extra millions are rushing in to the high-stakes, late-stage game. As these late-stage private companies digest these large fund raises, they are pushing profitability further and further into the future, as well as the proof that their business model actually works.”

WeWork, whose stated mission is “to elevate the world’s consciousness,” is a company that comes to mind. Investors seem to uncritically accept its “community adjusted EBITDA,” which ignores basic expenses like general and administrative, marketing and development costs, which are usually considered critical for daily operations. Neumann also felt it was okay to make millions on the side leasing properties to the company and to pursue his hobby by using company funds to buy a stake in a company that builds and operates wave pools for surfing.

WeWork is adding up to 1 million square feet of new office space every month. The long-term leases it signs can last 10 to 15 years and require the company to pay hundreds of millions of dollars in rent, even during economic downturns when vacancy rates rise. Its average customer has a lease of seven months and new customers are signing leases that average 20 months. WeWork also has nascent businesses in apartment rentals and private elementary schools. The company lost $1.9 billion in 2018 and $264 million in the first quarter in a booming economy. What happens in a recession?

WeWork has raised $12.8 billion over 14 funding rounds and is valued at $47 billion. As per Neumann, the company’s valuation has less to do with its revenue than its “energy and spirituality.”

There was strong demand for WeWork’s junk-rated bonds, priced in April last year and due in 2025, so the company increased its debt offering from $500 million to $702 million, which Neumann thinks is a lucky number. The bond is currently trading at 91 cents.

10. We were surprised to learn from SoftBank the original idea for the Vision Fund was for $30 billion. Only last minute did Masa Son change the investor presentation to reflect $100 billion ahead of a meeting with Arab investors, which became the most successful fundraise ever.

The Vision Fund started investing in May 2017 and has already deployed $80 billion across 82 companies. Which begs the question, how does one go from wanting to raise just $30 billion to investing nearly three times that amount in only two years, well ahead of the original five-year schedule? The Vision Fund executive was not as concerned, “Hedge funds look to ride the wave. Technology investing is going to change the wave.”

He said SoftBank is accelerating fundraising for Vision Fund II, which is to be seeded with $15 billion from the IPO proceeds of its mobile unit and a $20 billion rollover from the first fund. He said they are hoping Abu Dhabi’s Mubadala and Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund put in a combined $35 billion as well. We told him we don’t think Middle East money will flow into Masa’s coffers this time around. He won’t have any luck raising third-party capital.

The Saudis foray into Silicon Valley has been dumb and expensive. They ploughed $3.5 billion into Uber in 2016 at $48.77 a share, which makes them one of the biggest losers from the IPO. Their ill-timed $2.9 billion bet on Tesla is also underwater despite reports they slashed their exposure via a hedging deal. Taken together, they are nursing $1 billion in losses from those two investments. We suspect they may have lost their risk-seeking spirit. As it is, oil prices are off 20% in the past month.

Good thing the Vision Fund plans to borrow $4 billion against its stakes in Uber, Slack, and Guardant Health, said the executive. Last year, it took an $8 billion loan against its stake in Alibaba. As we sat listening, we evoked Warren Buffett’s wisdom, “When you combine ignorance and leverage, you get some pretty interesting results.” Borrowing against a company’s questionable net worth, as opposed to against cash flow and income, is, in effect, the same thing that US households were doing in the lead up to the housing crisis. On a consolidated basis, Softbank has amassed $143 billion of interest-bearing debt and $245 billion of total liabilities, far greater than its $97 billion market capitalization. The major global credit assessors rate the group at junk.

To be fair, the results so far stack in Masa’s favor. At SoftBank’s annual shareholder meeting, he revealed the fund has delivered an impressive 29% blended return for LPs so far. “I don’t like number two,” he said. “From my personality perspective, I can’t accept number two, I need to be number one. I’ve been like that since I was a kid.” Most of the Vision Fund’s gains—$12.2 billion—are on paper, driven primarily by Uber, WeWork, Indian hotel booking firm Oyo and Guardant Health. The fund marked up its stake in WeWork twice in the last year with repeated investments at increasing valuations. There is one IPO from the portfolio each month on average this year. “We are going to enter a true harvest season.”

Still, we were told Masa was baffled by Uber’s disappointing public debut and there is some concern about WeWork’s planned IPO as well. If both flop, this would be a negative signaling effect to prospective investors. Each $1 move in Uber’s share price swings the Vision Fund’s overall returns by more than $200 million, though it has been reported the fund has marked Uber up to a level higher than its current trading price. A spokesman for SoftBank told The Information, “We have a bullish view on Uber over the long-term. The company’s value will demonstrate itself over time.” In other words, let’s assign an imaginary happy value to our signature investment until markets are irrationally optimistic again—and we are not even in a crisis, yet. Marking to market used to be a simple affair. The Vision Fund is a classic case of buying high and then not having anywhere to go.

11. Masa was one of the largest investors during the late 1990’s dot-com boom. In January 2000, two months before the market peak, he owned more than 7% of the publicly listed value of the world’s internet companies, via more than 100 investments in what he called a “netbatsu,” a digital age variation of Japan’s old zaibatsu conglomerates. By March 2001, Masa had tripled his exposure and bet on 600 internet companies, but nearly all of them failed when the bubble burst. Masa lost more money in the 2000 tech crash than anyone else ever had—$70 billion. SoftBank’s stock fell 99%. Sometimes, we are prisoners of our own personal history.

12. We met with one founder who sold his cloud-based SaaS business to a software company in 2011. He recalled how difficult it was at the time to convince investors about the virtues of cloud. Now investors are in love with cloud stocks and willing to pay in excess of 20 times on a price to sales basis in some cases. He said investors are mistaken to think these businesses don’t depend on the economy and have revenues that are “unkillable.” Despite growing adoption, cloud stocks are fairly valued in his view. ServiceNow and Workday have ratios close to 15 and Salesforce’s is under 10.

13. Often each decade has a new theme. This decade was all about Internet Software & Services, which accounts for a quarter of the unicorn market cap. Marc Andreesen published his thesis on “Why Software Is Eating The World” in 2011 and his VC firm has been one of the biggest winners of the broad technological shift in which software companies are taking over large swathes of the economy. While more and more businesses and industries will be run on software and delivered as cloud services in the future, that is not where the best returns will be generated in the next decade in our view. In the first quarter, the number of early-stage funding deals for software companies fell 28%.

Sector-specific venture firms will be the big winners in the next cycle with fintech and health/biotech startups seeing the greatest valuation gains. As one investor told us, only two fintech companies are currently worth over $100 billion, PayPal and Alipay. Stripe and Square are next in line, but both companies were founded in 2009. In the coming decade, he expects at least 2-3 companies to exceed $100 billion valuation, 10 in the $50 billion range, and 30-40 worth around $10 billion. There are now 41 VC-backed fintech unicorns worth a combined $154 billion, according to CB Insights. Unlike consumer internet companies, fintech startups also have lower burn rates, which should help them in the next downturn to build more robust businesses as liquidity tightens.

There will be many new startups as the fintech wave is till early and the industry incumbents are ripe for disruption. It used to be that bank CEOs rise from the retail ranks but that is no longer the case. They do not have the background to build flashy experience layers and products that put the customer at the center. Digital banking companies have attracted millions of customer accounts.

14. There’s a liquidity crunch in China and the recent IPOs of US-listed Chinese companies have floundered, including electric carmaker Nio, online-brokerage Futu, and e-commerce companies Meituan-Dianping and Pinduoduo. Last year, 32 Chinese companies listed in the US, the highest number in nine years, falling 12% on average, underperforming the broader IPO market, which was down 1.9%, according to Renaissance Capital. More than 40 Chinese firms could list on the Nasdaq in 2019. A hedge fund manager we met in the Bay Area who frequently visits China said this is because liquidity is drying up onshore. Renminbi-denominated funds with state-backed investors have withdrawn from the market and smaller US dollar funds have also reined in investment. Companies are thus using Cayman VIE structures to raise capital. Chinese startups now account for just over 20% of $100 million funding rounds from 45% a year ago. The manager said for the first time in his career he is receiving inbound deals from mainland China which never used to happen. He is an investor in Bytedance, the world’s most valuable privately backed startup.

15. China is blitzscaling at another level. Consider the curious case of Luckin Coffee, founded in October 2017. The company raised $200 million Series A in June 2018. In December, Luckin raised another $200 million in Series B, valuing the Starbucks rival at $2.2 billion. In April, the company raised $150 million in a Series B+ from BlackRock and listed on the Nasdaq a month later pocketing $651 million. Luckin is now valued at $4.6 billion! Through aggressive promotions and coupons, the company posted a $475 million loss in 2018 with $125 million in revenue. In the first quarter, the loss narrowed to $85 million with total sales of $71 million. Luckin plans to more than double its locations from just over 2,000 to more than 4,500 by the end of this year. Customers use the Luckin app to “book” a coffee, arrive at the time it’s supposed to be ready, show a QR code, and walk away. What is interesting about Luckin’s story is that the founding team earlier took another business idea, UCAR, from incubation to $5.5 billion IPO in 18 months. Prior to that one of the co-founders, Yang Fei, was in jail for advertising fraud.

16. Silicon Valley has entered a “post-unicorn” era with the largest tech IPO deluge in years. Venture-backed companies accounted for 40% of all US IPOs in 2018, a 15-year high, with 33 unicorns exits, the highest annual total on record, for an aggregate deal value of $76 billion.

One founder who took his company public last fall said most companies aren’t ready to brace public markets. In fact, six of the 10 best-funded US tech startups to go public since 2015 have fallen from the peak levels they hit in private funding rounds before their stock debut.

17. Most founders are between the ages 25 to 40 and were not around for the 2000 tech bust—they have no idea what a bear market looks like. Many junior partners at VC firms have never seen an economic downturn either. Companies have stayed private longer and acquired crazy habits in this cycle. They are not used to being frugal and have only been trained to pursue growth—the metric that matters most to VCs.

We met some experienced founders and investors who worried that many companies will fail because they cannot quickly “flip the switch” from a focus on growth to cash conservation and profitability. As Drew Houston, CEO of Dropbox, remarked, “Cash is oxygen, and if you keep having to go to investors to fill up your scuba tank, then you can run out.” Most startups never have more than a year’s worth of runway in the bank. If valuations suddenly tank, they are going to be in serious trouble due to a lack of time and difficulty in fundraising.

In 2008, Sequoia Capital gave a presentation to the founders of all the private companies it had backed with the title, “RIP good times.” They were told to treat every dollar they spent as though it was their last. In a bear market, VCs pay more attention to stable, later-stage companies that have obvious potential, while floundering early-stage companies are left to their own. They invest more conservatively, demand more equity, while startups raise less money per round at lower valuations.

In 2000, one of Silicon Valley’s most prolific angel investors, Ron Conway, wrote an email to founders of his portfolio companies.

The capital market window is shut, including IPOs and VC Funding (VCs are looking at their existing portfolio funding needs—not new opportunities). Basically, the market is now looking for PtoP (Path to Profitability) instead of BtoC, BtoB! PtoE will prevail price to sales ratios! Lower your “burn rate” to raise at least 3-6 months more of funding via cost reductions, even if it means selective staff reductions and reduced marketing and G&A expenses. This is the equivalent to “raising an internal round” through cost reductions to buy you more time until you need to raise money again; hopefully when fundraising is more feasible. Be realistic on valuations—they will fall so be ready and willing to co-operate.

Nearly half, 48%, of dot-com companies founded since 1996 survived the crash and were still around by 2004, albeit at lower valuations.

18. Most venture capital financings use preferred stock with liquidation preferences, which gives investors a debt-like downside protection. When many of these preferreds pile on top of one another, the future payouts for investors can be wildly divergent depending on different valuations and whether the company clears certain preference hurdles. The only way to escape this cap table calcification is to actually go public, in which case all preferred shares are converted to common shares, and the liquidation preferences go away.

If we enter a prolonged bear market with private companies forced to raise a down round, as we expect, investors will discover many of their investments are actually worthless. VC returns will be heavily marked down. Many startup employees will also see their net worth decline materially, as they incorrectly valued their stock options, which form a major part of their compensation. Silicon Valley’s trademark optimism will turn to pessimism amid the financial market rout.

19. Practically everyone dismissed our dire outlook. The most common pushback to our view was that these warnings have been around for a few years now. Indeed, it was in 2015 when Bill Gurley said, “You’ll see some dead unicorns this year.” Sequoia’s Mike Moritz predicted, “There are a considerable number of unicorns that will become extinct.” All the while, an insane amount of money has been made. Gurley has even altered his view, saying last year, “You have to adjust to the reality and play the game on the field.” This is a classic sign of capitulation at the top.

For what it’s worth, our warning to readers has always been the same: the Uber IPO will kick off the endgame of Silicon Valley’s bubble. We return from our trip even more convinced of this.

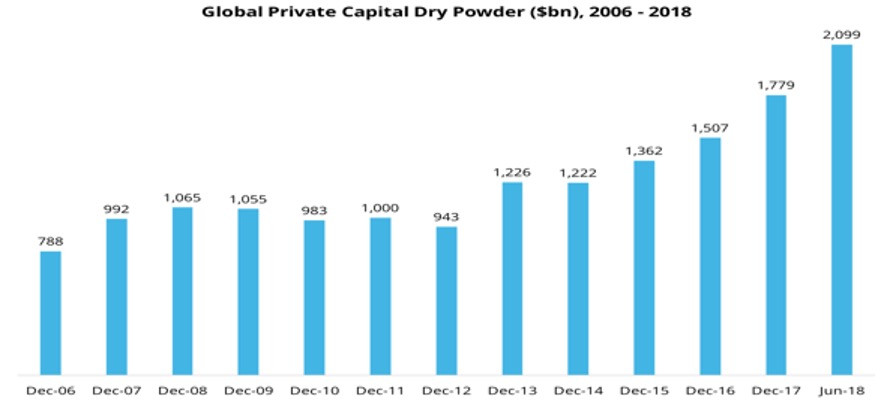

The other pushback we received was that there is simply too much capital sloshing around for company financing or valuations to be affected. We spoke with a number of allocators—endowments, pension plans, and sovereign wealth funds—who said they are underexposed to venture as an asset class and plan to increase their allocations. Yale, one of the most-watched institutional investors, has boosted venture capital to almost a fifth of its endowment (though we heard this is performance related and they are not putting new money to work). Corporate VCs are interested in doing more deals. Private capital dry powder has surpassed $2 trillion, a fifth of which is venture capital. The proportion targeting US startups is half that according to research firm Preqin, so about $200 billion.

We have a few comebacks for this. First, dry powder is always “high” at cycle peaks, as bullish sentiment feeds into greater capital commitments and venture funds are in no mood to turn it down. In 2000 and 2008, dry powder was also at record highs, but that did not prevent a Silicon Valley bust. Second, nothing changes sentiment like price. So once a cycle turns, not knowing how long it will last or how low valuations will fall, VCs hold back investing and call capital more slowly despite plenty of dry powder. This was confirmed to us by some VCs who were around during the dotcom bust.

It bears remembering that the median internal rate of return of some 100 venture capital funds launched in 2000 was negative 0.3%, the poorest ten-year rolling returns in venture capital history. Only 3.9% of them were able to achieve IRRs of 20% or more. The bigger funds, those over $500 million, struggled to return their initial capital net of management fees, expenses and carried interest.

Source: Preqin

20. These are the investment themes that stem from our analysis:

Short Silicon Valley Bank (SIVB): specializes in banking services for entrepreneurs and has helped fund more than 30,000 start-ups. The stock peaked last summer and could crash to 2012 levels, more than 70% below its current price.

Buy puts on SoftBank (9984): the heavily indebted company is the most levered play to the US and China’s tech cycle.

Short companies with negative cash flow that also have less than twelve months of cash on hand. Snap, Luckin Coffee, etc.

Short China Internet stocks: China has the world’s most centralized internet and the government is tightening regulation and supervision. BATs—Baidu, Alibaba and Tencent—are also the most active VCs in China and will get hurt as valuations cool.

Short WeWork bonds: the business model for the most profligate startup could spiral when the economy weakens, accelerating losses could even be an existential threat for the company.

Short cloud stocks: cloud-based SaaS companies are among the most expensive group in the stock market and valuations will crater when tech spending slows in the next downturn.

Short basket of food-delivery players: Grubhub, Just Eat, Delivery Hero, and Takeaway.com.

Short Business Development Companies (BDCs): these provide speculative capital for growth or acquisitions to small and medium-sized businesses, hold 90% or more of their assets in debt investments and pay large dividends to shareholders, despite poor underwriting ability.

Short Japanese Banks: the tech sector has driven US CLO issuance and accounts for 25% of the CLO market today, from 8% a few years ago; Japanese banks piled up on CLOs for yield and are a good proxy given own weak fundamentals.

Long Bitcoin: the cryptocurrency should thrive in a time of chaos and confusion.

It has been well said: “Nothing important has ever been built without irrational exuberance.” It requires a mania and new-era thinking to finance the building of new ideas, whether its railroads or ride-hailing companies. Much of the capital invested in the dotcom bubble was lost but it bore the backbone for the internet and software, which has changed all of our lives. Similarly, the current mania will yield enormous losses, but it will also have provided us with technologies and services that we cannot imagine living without.

Photo: Wikipedia