Our job is not to see the future; it’s to see the present very clearly.

On November 24, Marko Papic, chief strategist at Clocktower Group, joined us in our virtual salon to sketch out the major themes that will underpin the “twenties.” The intention was to identify the broad narratives that will define the next decade and the investment strategies to accompany them.

The five paradigms we considered are: balanced multipolarity, generational conflict, China’s introspection, atoms over bits, and climate change as an investment thesis.

This is a summary of our discussion.

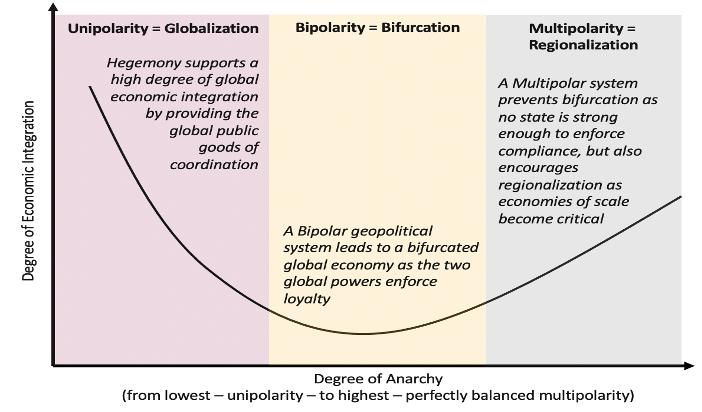

Theme 1: Balanced Multipolarity

When historians look back at the 2010s with some distance and perspective, they will see it as a decade during which geopolitical risks surprised to the upside—the first violent annexation of European territory since World War II (Crimea), Middle East violence, European political imbroglio, and, of course US-China tensions—whereas domestic political risks surprised to the downside.

Papic thinks that the balance between geopolitical and domestic risks will flip in the 2020s.

The next decade will see a surprising geopolitical balance emerge. First, states like Russia and China have put aside a century of enmity and begun to balance against the US. Second, the US has weakened the sinews of its Cold War alliance structure ever so slightly, causing its allies to drift, form alternate structures, and think geopolitically for themselves. Third, powerful emerging markets have begun to act independent of the Western alliance structure, flirting with China, the US, and Europe simultaneously.

The global distribution of power favors a rivalry more akin to the nineteenth century “Great Game” between superpowers than the neatly bifurcated world of the Cold War era.

The twenties will see a rotation of risk from the geopolitical realm to the political, from the international sphere to the domestic. The investment significance of this shift will be profound. The volatility of the 2010s will give way to somewhat calmer geopolitical waters in the 2020s.

Source: Clocktower Group

“If the last decade was a messy interregnum, balanced multipolarity is a far more stable system,” says Papic. “This is positive as it means that a conflict between major powers will remain unlikely.”

A risk to this view is that China suffers an internal crisis, allowing the US to restore its undisputed global leadership. Even in that case, however, there is no guarantee that the current isolationist narrative would not remain popular over the course of next ten years.

Investors should therefore not expect the twenties to see the collapse of the EU, Canada, the UK, or any other political entity. Instead, the world will see the emergence of spheres of influence, some modeled on the very political integration of the EU that many have spent the last decade expecting to collapse.

For all its headline-hogging, Papic thinks geopolitics will have muted impact on asset prices. Domestic monetary and fiscal policy will be the dominant drivers.

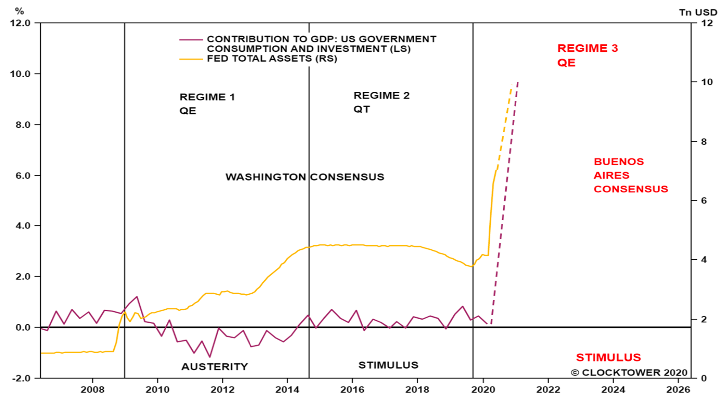

Theme 2: Generational Conflict

In the US, today’s youth are significantly worse off than their counterparts over the past six decades. While global Millennials are not as severely indebted as their US counterparts, they still struggle to climb the housing ladder (Commonwealth economies and Scandinavia) or to secure permanent, contract, employment (continental Europe and Japan).

Then there is the issue of the cultural, social, and behavioral chasm between the Baby Boomer generation and the Millennial and Gen-Z cohorts. These issues set the stage for a 1968 like explosion of unrest that may not necessarily be violent but will certainly have policy implications as the younger cohorts begin to define the median voter.

The next decade will see a massive wealth transfer between Baby Boomers and the younger cohorts. Papic believes this transfer will not be an orderly passage of wealth from parents to children.

Instead, policymakers will respond to the generational conflict by using the time-tested redistribution of inflationary policies. The median voter will demand an ever-lower interest rate and ever higher fiscal outlays. “We are at the cusp of a paradigm shift in monetary and fiscal policy, says Papic. “The odds that politicians reverse massive fiscal and monetary stimulus or that central banks turn the screws of monetary policy at the first sign of higher inflation are low.”

Source: Refinitive and Clocktower Group

The median voter in America is, from 2020 onwards, a debt-ridden Millennial facing stagnant wages and massively appreciated middle class goods. He or she is the price maker in the political marketplace. Politicians are price takers. In broad terms, this means policies will begin to shift in favor of the Millennial generation, benefiting debtors versus savers.

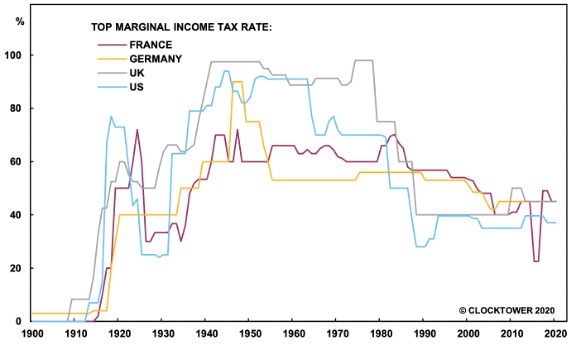

One such policy that favors debtors over savers will be much higher top marginal tax rates. Tax rates rose dramatically after World War I, but then fell back in the 1920s. However, the Great Depression saw top marginal rates across the world skyrocket. They stayed elevated throughout the Cold War.

Not only were rates elevated, but the tax rate curve was much steeper in the post-World War II era than today. It is likely that we will see the Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez proposal of 70 percent top marginal tax rate within this decade. And given Biden’s proposal that capital gains and dividends are taxed at the personal income tax rate, this would substantively alter the tax implications of investing in private and public markets.

Source: Capital in the 21st Century (T. Piketty), KPMG, and Clocktower Group

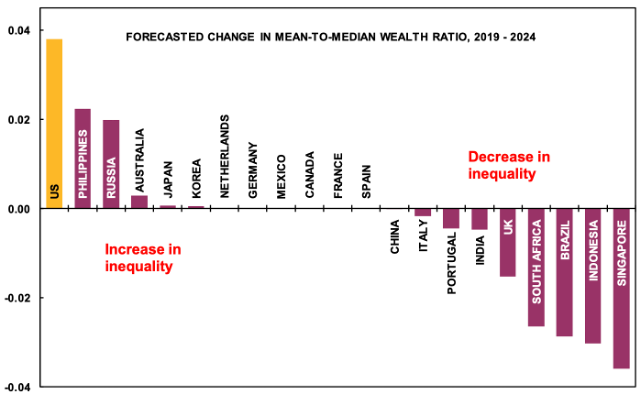

The ownership of equities by the top 1 percent has grown from 42.3 percent in 1989 to 53.5 percent in 2019 while the ownership of stocks by the under 40 age cohort has declined from a respectable 11.1 percent in 1989 to just 3.4 percent in 2019. The top 10 percent of US wealth percentile therefore owns 88 percent of all stocks and mutual fund shares owned in the country.

All this would be relatively non-controversial if the government rebalanced intergenerational inequality through welfare transfers. But that is not the case in the US. Hence, Papic believes that the generational wealth transfer is only going to see income inequality widen and social mobility decline in the US over the next decade.

In the end, the 2020s will end the same way as the 1970s, with inflation getting away from the comfortable 2 to 4 percent range and a deep political malaise enveloping the country. This will build up the political capital for a new set of politicians to reassert control over monetary and fiscal policy.

Source: Credit Suisse Global Wealth and Clocktower Group

Theme 3: An Introspective China

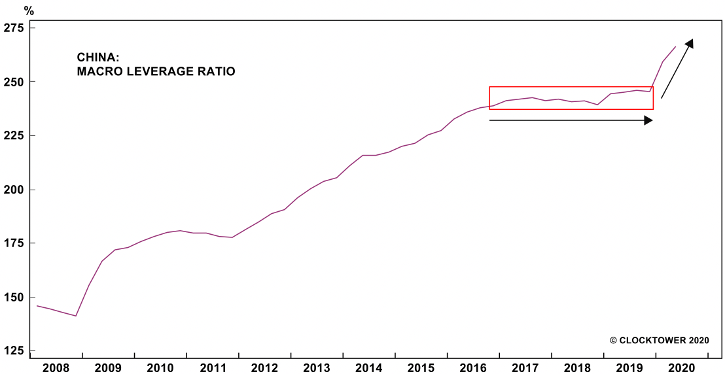

The 2010s were the decade where China became the dominant engine of global growth, but at the expense of domestic supply side reforms. The 2008 financial crisis and the subsequent collapse in global trade forced China to hastily stimulate domestic demand by putting local governments in the driver seat.

In the early 2010s, the proliferation of local government financing vehicles (LGFVs) became a defining feature of the Chinese economy, creating spectacular growth in infrastructure and leading to a dramatic rise in urbanization. China’s countercyclical stimulus had been a windfall for the rest of the world, driving bouts of outperformance in commodities and emerging markets when the other engines of growth stalled.

That said, Chinese local governments’ reckless spending on projects regardless of their intrinsic value has led to rampant debt accumulation, crowding out financial resources for the private sector, and presenting a systemic risk to domestic financial stability.

As such, deleveraging took over debt expansion as the preeminent macro theme in China in the second half of the 2010s, with Beijing determined to restore fiscal discipline within local governments. Most importantly, the latest reform push to liberalize the interest rate system and support private-owned enterprises (POEs) have demonstrated policymakers’ resolve to let the market, rather than the government, play a “decisive” role in allocating economic resources.

The pandemic has reversed Beijing’s progress on financial de-risking since 2017. As such, Papic argues Chinese policymakers will attempt to undertake their own version of laissez faire reforms over the next decade.

China will focus on optimizing domestic resource allocation and enhancing productivity, with the ultimate goal of escaping the middle-income trap. China is clearly shifting to a service-led economy powered by rising GDP per capita. Beijing’s aspiration to move up the value chain indicates increasing investment into the tech sector. An advanced tech sector would not only help China escape the middle-income trap, but also address the national security threat presented by US sanctions.

Papic sees China turning inwards and staging a strategic retreat on the geopolitical front to address more urgent economic challenges. China will still defend its red lines of sovereignty over Taiwan, Tibet, and the South China Seas. But its foreign policy may become surprisingly tame after a decade of aggressive posturing in Asia-Pacific.

The overarching lesson from China’s material constraints through the prism of its “three teachers”—China’s dynastic history, Japan, and the Soviet Union—is the same: reform or perish.

Source: Wind, Cass, and Clocktower Group

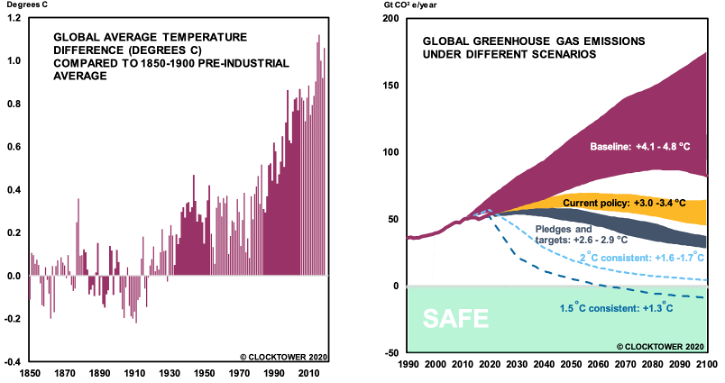

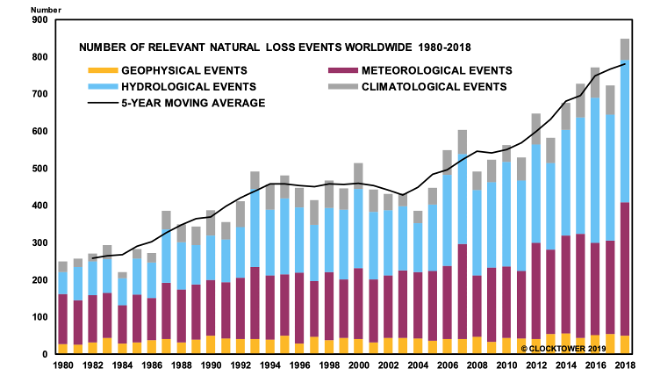

Theme 4: Climate Change

Humans are generating around 40 gigatons (Gt) of CO2 per year, a figure that will double by 2050, ceteris paribus. The scientific consensus has determined that in order to keep global warming as close to the 1.5 °C increase above pre-industrial levels—the current level of “warming”—emissions should be reduced to essentially zero by 2050.

Papic finds little evidence that the world will adjust its emissions profile over the next decade. But the climate change narrative will spur a major increase in fiscal outlays towards research and development.

President-elect Joe Biden pledged to spend $2 trillion on climate change. Europe has pledged to spend over €135 billion on the same effort, with the EU Commissioner Urusla von der Leyen referring to the effort as “Europe’s Man on the Moon moment.” Climate change is therefore significant as it gives Germany, in particular, a moral reason to break their austerity fetish.

The “green agenda” will create a liquid EMU-wide bond market that boosts euro’s credentials as a reserve currency. It becomes a way to engender what are essentially transfers payments between member states, helping to resolve many of the inefficiencies of the common currency by stealth.

Source: Met Office, Climate Analytics, New Climate Institute

Whether a surge in “green spending” makes sense is irrelevant, according to Papic. He compares it to the US decision to put the man on the Moon, which he thinks was “one of the most wasteful enterprises in human history.”

Why does he think that? Because we have not been back to the moon since 1972. Had it been relevant for the human race he says, we would have been back. However, the endeavor required such a dramatic increase in funding for basic research and development that we are still coasting on the technological and productivity benefits today of this “wasteful” effort.

“The point here is that even if climate change were a conspiracy theory concocted by globalist elites to force us all to use paper straws and drive European hatchbacks,” jokes Papic, “the effort to fight it will likely result in ancillary technological innovation that will impact total factor productively positively.”

Countries that get an early jump on this spending could dominate the twenty-first century technologically as they reap the first-mover advantage. The technological innovation that flows from that is unknown, but likely to be groundbreaking in the fields of transportation, energy, and agriculture.

The best way to take advantage of these opportunities will be in the private markets space, particularly early-stage investing, focusing on technology and data companies that service the climate change narrative.

Socially responsible investing (ESG) will also continue to grow in prominence, as will other forms of investing that directly focus on mitigation of climate change (issuance of green bonds, for example).

Source: MunichRe

Theme 5: Atoms over Bits

The US has seen much innovation in the realm of bits in the past decade, but little in the realm of atoms. This resulted in the extraordinary outperformance of US tech relative to the rest of the world. Marko believes this is likely to end in the 2020s for several reasons.

First, technologies such as 5G and blockchain will allow software applications to be extended further to the “edge,” the internet-connected hardware devices that make up the internet-of-things. But that will also move the innovation to the edge devices—essentially consumer electronics—and away from web 2.0 platforms.

Second, the multipolar geopolitical world will be replicated on the internet, with a “splinternet” future limiting the TAM available to the US technology behemoths. One version of this future may include a bifurcated world, split into Amazon and Alibaba technology camps. But we suspect that there will be more than just two splinternets, potentially further limiting the TAM available to US tech companies.

Third, the coronavirus pandemic has brought to bear America’s lack of innovation in manufacturing. America was dependent on imports of cheap medical devices and healthcare supplies. Another ignominy for America was seeing Germany use its prowess in biotech and pharma to mass produce a functional COVID- 19 test.

Papic believes the next decade will see the government take back a leading role in manufacturing.

Such efforts will skew the balance of innovation back towards atoms over bits (except in finance and healthcare which remain dominated by legacy businesses). He thinks investors should begin rotating out of tech-heavy US stock market and into markets with a larger representation of industrials.

Investment Ideas

Short US dollar: A multipolar geopolitical system is likely to lead to a multipolar currency system. While the US remains the most powerful country in the world with the most liquid public market, it has also begun to use those attributes for geopolitical gains. No longer is access to its markets magnanimous and geopolitically neutral.

The US has widened who it denies access to the dollar system from “rogue states” like Iran and North Korea to other great powers like Russia and now even China. This has already motivated a search for an alternative. Ironically, yet again, we expect the euro to fill in some of the void, catching up to at least its pre-1990s level of reserve currency status.

Papic argues long-term investors should favor a basket of euro, Swiss franc, and Chinese yuan, over the US dollar, British pound or Japanese yen.

Favor Domestic Over Multi-National: Whenever possible, favor domestically (or regionally) oriented firms over multi-national corporations. The easiest way to play this is to simply go long small caps over large caps in whatever equity market one is investing as small cap stocks tend to be domestically oriented.

Underweight US: US equities are likely to massively underperform the rest of the world over the course of the 2020s, with inflation-adjusted equity returns on S&P 500 likely to disappoint, like in the 1970s. However, Papic warned to be careful in trying to time this shift.

He is bullish on Europe: “The EU is not just going to survive in the 2020s, it will thrive. Even the emergence of nationalist populists will not cause fracturing.”

Long Gold: Gold is an obvious hedge against a decade of inflation, as are Treasury inflation-protected securities (TIPS). The view that inflation is likely to re-emerge over the next decade is certainly becoming more prominent and popular, but it is nowhere near priced in by the market, with the 5-year, 5-year forward pricing-in merely 1.5 percent inflation in the second half of the 2020s.

Long Semi Capex: A de-globalized world split into spheres of influence will have to see the re- wiring of supply chains. Specifically, semiconductor supply chain will have to be completely re-wired as China—previously the world’s workshop—and the US disentangle.

Long Renewables: The S&P Global Clean Energy Index has decoupled from the price of conventional energy, since about 2016, and is breaking out this year. A strategic long makes sense. A counter intuitive idea is also to buy commodities which stand to benefit from the de-carbonization of the global economy and a future of electric vehicles (copper, lithium).

Long Oil and Energy Stocks: In the all-important US shale patch, the rig count has collapsed to pre-revolution lows. With oil prices below the average shale breakeven price, recovery in shale production will take some time. Meanwhile, there’s more evidence populations are becoming desensitized to Covid-19 with mobility indices not falling as much as in the past with rising cases. This should buoy demand.

There is a new geopolitical tailwind for oil prices as America rejoining the Iran nuclear deal will result in greater Israeli and Gulf insecurity. The possibility of them acting unilaterally against Iran will go up dramatically. Papic likes oil transportation stocks.

Photo: Unsplash