Thank goodness for Carlota Perez. In our grim period the esteemed Venezuelan economist, now in her eighties, is a spirit-lifter where things seem irredeemably complex. Her life’s work on the nature of techno-economic paradigm shifts throws water on our burning questions about the future.

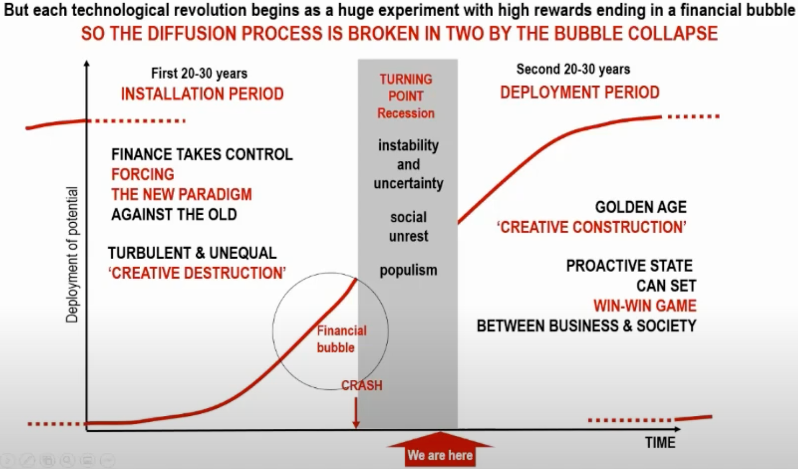

In Perez’s particularly useful framing of the technological cycle, there are three phases: (1) a disruptive period of “installation” brought on by new technology, (2) a transitional phase or “turning point,” as society confronts countervailing pressures to technology-driven change, and (3) “deployment,” a period of great socioeconomic progress as the technology achieves wide adoption and use.

Her central contention is that it takes an exceptionally long time from original invention to the golden age when we unlock the true potential of the technology. For the information and communications technology (ICT) revolution that began in the seventies, the best days are still ahead.

Source: Carlota Perez, “Technological Revolutions and Financial Capital: The Dynamics of Bubbles and Golden Ages”

Installation

As new technology comes to market and infrastructure is built, this installation phase lasts twenty to thirty years or more.

Technology may need to be pushed to market at first if customers don’t understand the benefits. Picture personal computers in the seventies or the internet in the nineties. The possibilities of a radical innovation are so difficult to envision that even those who carry them out grossly underestimate their potential.

“There is no reason anyone would want a computer in their home,” insisted Ken Olson, president of Digital Equipment Corp., in 1977. In 1995, Robert Metcalfe, internet pioneer and formulator of Metcalfe’s law, predicted in 1995 that the internet will “catastrophically collapse.”

Once a story coheres around the disruptive power of a trend, speculative capital builds the requisite infrastructure. This energy turns into a bubble: overbuilding happened with canals (1797), railways (1847), and telecom infrastructure (2000).

Telecom companies plied more than $500 billion into laying fiber-optic cable, switches, and wireless networks in the run-up to the dotcom crash. Capacity vastly outstripped demand (though the foundation had been laid for widespread high-speed connectivity).

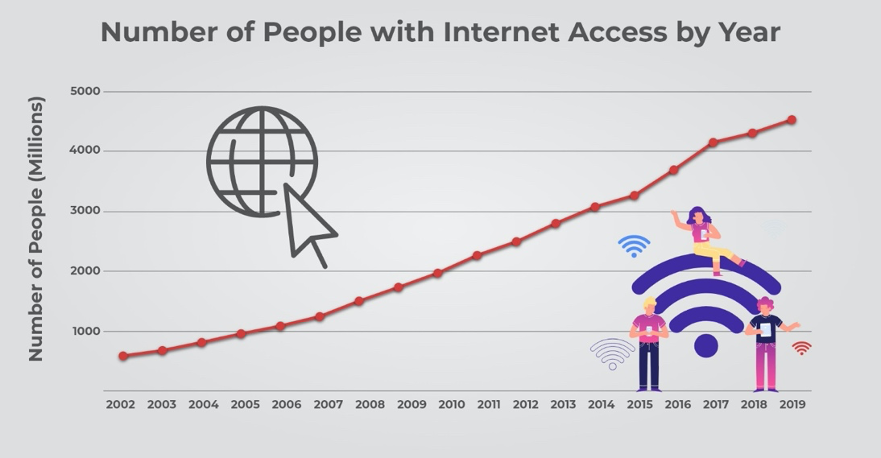

There are now 4.6 billion internet users compared to 400 million in 2000. That’s 59 percent of the globe. The internet, along with smartphones, has been installed, if you like, nearly everywhere.

About 100 million people bought smartphones in 2007 when Apple launched the iPhone. Now 1.5 billion smartphones are sold every year. Nearly 85 percent of all mobile users in America own a smartphone, up from 27 percent in 2010. The internet’s in everyone’s pocket.

Source: Digital Trends

Installation is a period of creative destruction. The dominant industries of the previous revolution struggle to keep up with the agile new entrepreneurs and innovators; their businesses mature and decline. Failure to adapt leads to massive job losses and damage to the communities they used to boost. A polarization between the new and old economy sets in.

Consider Amazon’s disruption of traditional retail, the bankruptcy of Detroit vis-a-vis Silicon Valley’s ascent, and Tesla’s value outstripping the combined automakers’. Old stalwarts are replaced by new giants.

Monopolies and oligopolies typically form during the installation period, according to Perez. J.P. Morgan united the steelmakers under one US Steel umbrella. The US automobile industry, forty-strong in the 1910s, ended up an oligopoly of only three. The same happened, in one way or another, to oil, chemicals, electrical appliances, and retail chains.

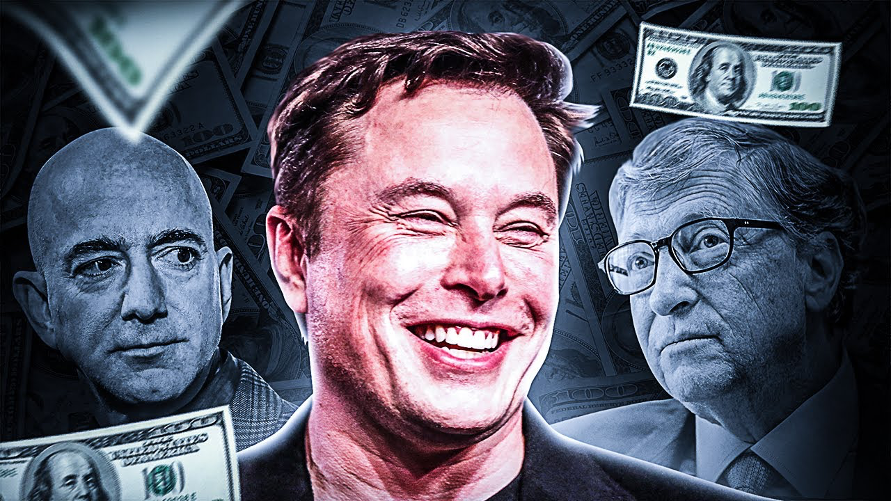

The very nature of technological revolutions, the way they diffuse, leads to winner-takes-all. Inequality worsens as the economic benefits accrue to a small elite.

Other technologies installed include the smartphone, cloud computing, artificial intelligence, alternative energy, DNA sequencing, CRISPR-Cas9, 3D printing, and blockchain.

Source: MarketWatch

Turning Point

It is “an old pattern in economic history,” historian John Steele Gordon explains. “Whenever a major new force—whether a product or technology—enters the economic arena, two things happen. First, enormous fortunes are created by entrepreneurs who successfully exploit the new, largely unregulated niches that have opened up. Second, the effects of the new force run up against the public interest and the rights of others.”

Midway through the technological revolution, resultant societal problems catch the attention of government as economic inequality rears its head. A crisis usually unfolds and marks Perez’s turning point, a messy and difficult period leading to a shift in culture, values, and aspiration.

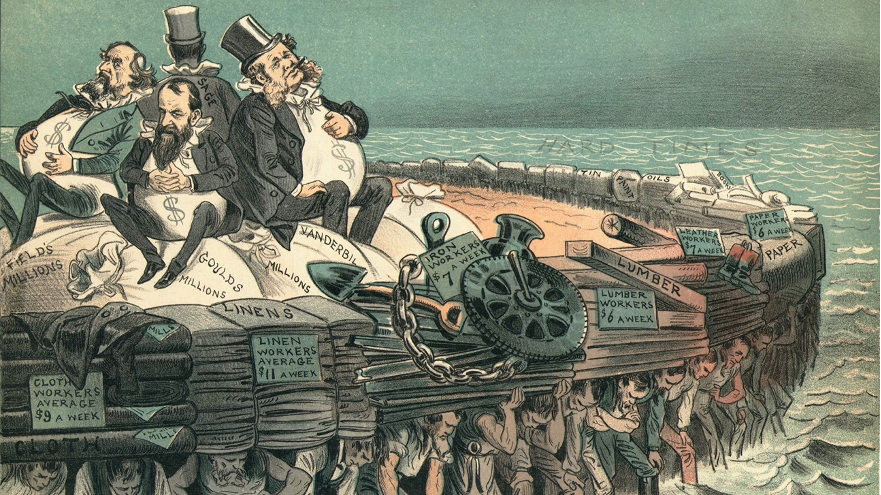

In the late nineteenth century, America was firmly planted in the Gilded Age. The entrepreneurs popularized as robber barons built business empires and amassed fortunes, spearheading America’s transformation from agricultural to industrial.

The burgeoning agrarian woes of the early 1890s combined with the financial and industrial depression of 1893 led to the political realignment of 1896 and the presidency of William McKinley. What followed was the widespread social activism and political reform of the Progressive Era.

Progressive reformers harnessed the power of government to increase antitrust enforcement, outlaw unethical business practices, and counteract the negative social effects of industrialization. Protections for workers and consumers were strengthened, and white women had achieved the right to vote.

At this stage, the top 1 percent of society was receiving 25 percent of the income. The glaring inequalities of wealth and privilege on display in the Roaring Twenties’ were supplanted by the New Deal following the Great Depression. By the 1950s, it was down to 10 percent. The interests of business and society converged.

The new welfare state freed up discretionary income. Working-class people could become homeowners and consumers. As companies paid high salaries and high taxes, it all contributed to increasing domestic demand and a growing middle class. This created the conditions for good profits and decent livelihoods. The years from 1950 through to 1970 were deemed the golden age of capitalism.

Source: “The Protectors of our Industries,” an 1883 cartoon symbolizing robber barons in the Gilded Age, by Joseph Keppler

Based on Perez’s model, we believe the pandemic is the turning point of our present technological revolution. From the Black Death to Covid-19, epidemics have shaped history in part because they hold up the mirror to human beings as to who we really are, warts and all.

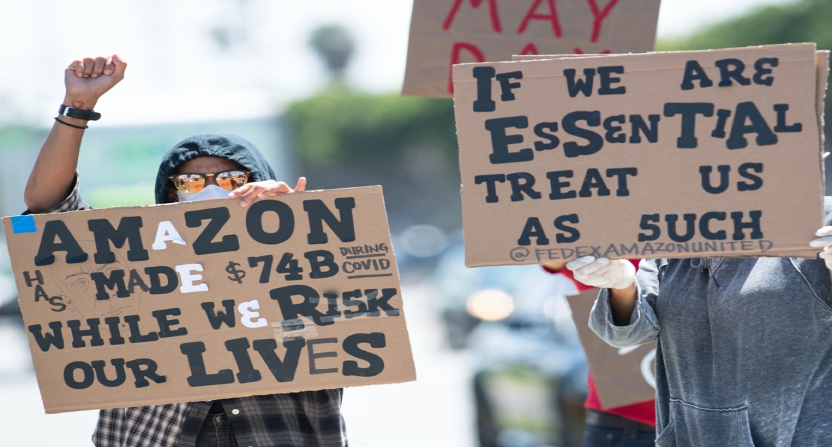

Present-day America has a lot in common with the bygone era of grotesque inequality and monopoly. The technology-driven innovations improving daily life came with outsized wealth creation, exploitative labor practices, and non-competitive markets.

A new consensus is emerging, however, that business and government are to act upon the most socially cohesive and environmentally responsible paths. The coronavirus shone a harsh light on the class divide and neglect of the natural environment.

“We need a great reset of capitalism,” admits Klaus Schwab, founder and chairman of the World Economic Forum, “to create a healthier, more equitable, and more prosperous future.” Pursuing profits is no longer the ultimate goal of all business activities. The club for global elites has set a new agenda to steer the market toward fairer outcomes and create the conditions for a “stakeholder economy.”

Ronald Reagan said that “government is not the solution to our problem; government is the problem.” This is true in installation. During each turning point, the government morphs to become the only expected solution. The ground is laid for the economy to reinvent itself, typically in the form of higher wages and taxes, more regulation, and a redesign of the social contract to provide an adequate safety net.

Outdated welfare systems are unable to account for a world where temporary, irregular work has become normal and frequent, where life expectancy has increased and medical costs have soared. Some form of basic income would maintain a minimum threshold, enough to cover food, transport, and basic shelter—an arrangement the government benefits from in the form of taxes once the receiver earns enough.

Serving not only as a safety cushion for irregular income streams, a basic income provides subsistence cash flow to those training or volunteering and a monetary launching pad for new artists and innovators. It helps parents with babies and the elderly with insufficient pensions. With job seekers afforded the time to find a job that matches their skills and aspirations, we can expect productivity to increase.

Dire poverty, which pushes the rejected, ignored and left-behind in myriad untoward directions—with society clumsily picking up the tab for policing, jails and health care—would be replaced in many cases by dignity.

Source: Shutterstock

We can make out during this transitional period the broad contours of a “good life”: a new settlement between technology, people, society, and nature. From the 1850s, it was urban living in the cities of Victorian Britain, it was cosmopolitan living from the 1880s during the Belle Époque, and the American way of life from the 1950s.

It was during the last turning point, in one of the worst years of the Great Depression, that historian James Truslow Adams coined the “American Dream.” His 1931 book Epic of America described it as “that dream of a land in which life should be better and richer and fuller for everyone, with opportunity for each according to ability or achievement.”

Even after 50 years, the ICT revolution is far from complete. It hasn’t fully changed society or our way of life to the extent that earlier techno-economic paradigm shifts have. But as we are beyond the installation period and are now passing a historic, pandemic-induced turning point, it is starting to.

Perez believes our notion of the good life is moving away from mass consumption and toward “smart green,” which focuses on health, nutrition, exercise, creativity, experiences, community participation, and access (sharing or rental) rather than possession. (We would add that it will also be more digitally native.)

If she’s right, it means a sustained shift from products to services—as has already happened with music, books and film—from tangibles to intangibles—from plants, machinery and energy-intensive capex to software and intellectual property—and from mass production to customization as niche markets are carved out.

Source: Wikipedia

Deployment

“The common belief that technology moves much faster these days than it ever did before is largely a delusion,” observed influential writer and management consultant Peter Drucker. “What has changed, and changed profoundly, is our awareness of change.” Technological progress, itself, is slow.

Thomas Edison brought electric light to parts of Manhattan in 1882. But most Americans still lit their homes with gas light and candles after the turn of the century. Only by 1925 did half of all homes in the US have electric power.

And while oil, automobiles, highways and mass production underpinned a technology system ripe for a leap in productivity from the 1910s, its wealth-creating power was only revealed during World War II and in the post-war suburbanization boom.

This pattern repeats with ICT and its remaining potential for transforming all other industries and activities.

The next two decades or so constitute the period of deployment, during which the new technologies spread their transformative power across the economy and the benefits reach broader society.

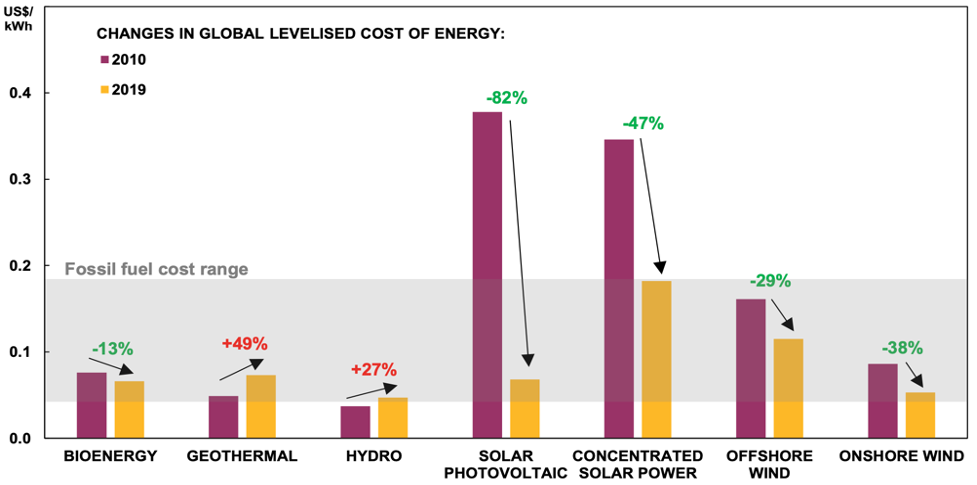

Once deployment begins, there is excess infrastructure (from overinvestment in installation) and the cost to use it is low. Consider broadband data, alternative energy, battery technology, and genome sequencing, the costs of all of which experienced sharp drops.

Technology in this phase is pulled by customers. This is all the more true in a pandemic, which is forcing everybody to embrace the installed digital technologies.

Almost every business is using cloud-based services, artificial intelligence is making sense of complex patterns in vast pools of data, the fastest vaccine development in history was made possible by genome sequencing, there is unprecedented interest in renewable energy, and we are seeing institutional acceptance of bitcoin.

Source: Clocktower Group

Deployment is a period for creative reconstruction. Each time, just as now, it appeared like a new world was dawning.

The golden ages of the past were unleashed by bold and determined policies that were imaginative and well suited to realize the transformative potential that each technological revolution installed. As we look ahead, a green socially sustainable golden age is technologically possible. This is the investment zeitgeist of our time.

“Capitalism only gives such opportunities to society once or twice in a century,” says Perez. “Let us make sure we do not waste this one.”

Governments are already starting to change the narrative by turning the environmental crisis from an economic problem into an economic opportunity. The debate is no longer framed as sustainability versus growth, but rather that it is mission-critical to promote a major switch in production patterns and lifestyles, which will create new sources of employment and well-being.

Over the next decade, China, the EU and Japan plan to spend around $2.2 trillion on building “green” urban infrastructure and creating incentives for industries to improve their environmental, social, and governance (ESG) track record. The Biden Administration promised to spend $2 trillion over the next four years to escalate the use of clean energy in transportation, electricity generation, and construction.

“These are the most critical investments we can make for the long-term health and vitality of both the American economy and the physical health and safety of the American people,” Biden said, recommitting the US to the Paris climate accord on his first day in the Oval Office.

November’s UN climate conference in Glasgow will provide a focal point for a new wave of long-term climate targets, many of which will be aimed at achieving net-zero emissions by mid-century or sooner.

Source: Getty Images

The Best Days Are Still Ahead

Even if we may not fully understand the forces that operate on us, it’s nice to have an all-encompassing theory that weaves our past and future into our present experience.

Rather than a dystopian, divisive future, Perez makes us wonder: are we on the cusp of a new golden age? The present ICT revolution still has ten to twenty years left to realize its potential.

It takes a long time for the new technological paradigm to propagate and be assimilated. For the past thirty years, the internet was just being “installed.” So were other breakthrough technologies. As we enter the deployment phase, now is the time to reap the full rewards. Semis will keep benefiting from rising tech adoption across all industries. Memory chips are a commodity in the prevailing technological paradigm.

Admittedly, our socioeconomic and political choices determine the path of progress, and technology has of course changed the world. But, damn, when you think about it from Perez’s perspective, we’re just getting started, and that compels us to finish with a punchy forecast: the best is yet to come.

Photo: Shutterstock