If you listen to Anthony Fauci, the top US infectious disease official, the pandemic won’t be around for “a lot longer” thanks to speedy vaccine development. “The end is in sight,” he says, one year in, after Covid-19 has already infected over 100 million people and claimed more than two million lives.

The history of pandemics teaches us to expect otherwise.

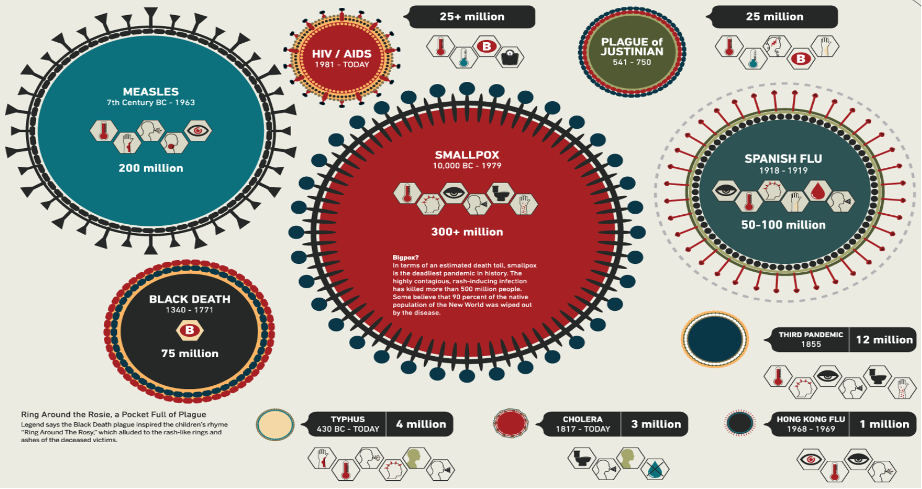

The Black Death pandemic struck in 1346, ravaging the world through the early 1350s, causing as many as 200 million deaths. Many countries suffered recurring outbreaks every decade or so until the eighteenth century. Scientists are still left wondering how the deadly pandemic subsided.

The 1890 Russian flu, with a coronavirus as the culprit, killed 1 million people globally. Yearly outbreaks continued through 1895 until the population acquired partial immunity. It’s still with us today, mostly causing a common cold.

The 1918 Spanish flu infected 500 million people, roughly one-third of the world’s population, and killed some 50 million. That global pandemic lasted for two years until natural infections conferred immunity on those who recovered. A particular strain of the offending H1N1 virus became endemic, circulating for another forty years.

It took another pandemic, the Asian flu outbreak in 1957, to extinguish most of the 1918 strain. The H2N2 influenza virus killed more than one million people and, through a series of mutations, continued to be transmitted until 1967.

The virus eventually morphed into a new influenza A subtype, H3N2, which gave rise to the 1968 flu pandemic. Vaccines limited the spread, although an estimated one million to four million people lost their lives. Descendants of the H3N2 still circulate as a seasonal flu.

Whether bacterial, viral or parasitic, virtually every disease pathogen that has affected people over the centuries is still with us, because it is nearly impossible to fully eradicate them. Nature is still the best engineer.

Source: Around the World (The Atlas for Today)

From what we know, pandemics only end when herd immunity is achieved through natural infection or vaccination. That means the Covid-19 pandemic’s course depends greatly on how long the immune system stays protective after vaccination or recovery from infection.

The outlook is uninspiring.

Scientists initially estimated that 60 to 70 percent of the population needed to acquire resistance to the coronavirus to banish it. Now that number has been revised to 85 percent. The more transmissible a pathogen, the more people must become immune in order to stop it. Meanwhile, the rate of reinfections hints that immunity to Covid-19 may be fragile and wane quickly.

The majority of studies have found that antibodies fade over time. Two defenses in particular, killer T cells and B cells (antibody-producing plasma cells), persist for six months after the initial infection.

The SARS-CoV-2 virus, which gives us Covid-19, is spread largely by asymptomatic carriers, who produce low—sometimes even undetectable—levels of antibodies. They may be the most susceptible to reinfection. Despite months of exposure, antibody surveys found a low seroprevalence, with less than 10 percent of the populace armed with antibodies. This is an impediment to herd immunity.

Vaccines don’t shield the body from infection, but by protecting the vast majority from severe disease, they serve to limit deaths and hospitalizations. The long-term immune response post-vaccination, however, remains to be seen.

Several new highly infectious strains of the virus are circulating globally. The UK variant has been found in at least 31 other countries. New variants can evade immune responses triggered by vaccines and previous infection. Recent studies suggest the vaccines are not effective against the variant found in South Africa. Science is always a step behind the evolving virus.

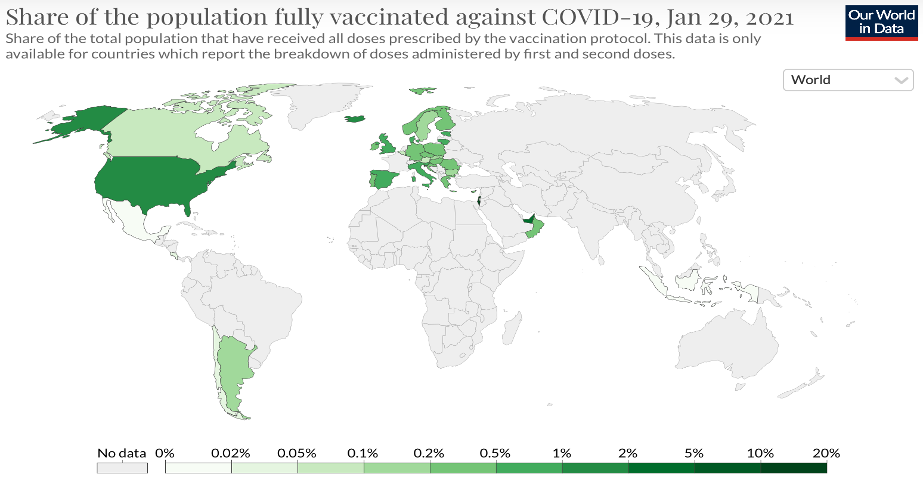

More than 90 million vaccine doses have been administered in 62 countries. An average of 4.39 million shots take place every day. Still, there just isn’t enough to inoculate some 7.8 billion people.

Oxfam has warned that 61 percent of the global population will not have a vaccine until at least 2022. Rich countries representing merely 13 percent of the world’s population have reserved more than half the supply of leading vaccines. The EU has signed enough future procurement contracts to vaccinate all its citizens twice over; the US has locked in four times the doses it needs, and Canada six.

Pfizer and Moderna’s 400 million doses destined for the US this summer cover 200 million people. Johnson & Johnson will provide another 100 million doses by June. That’s enough for widespread immunity by 2022 if the rollout goes smoothly. States face big logistical challenges. Only five million Americans have completed the vaccination regimen so far.

China curbed the virus faster than any other country. Hospitals were built in days to treat the rapidly rising cases, and a national mobilization eased desperate shortfalls of equipment and medical workers. But China’s vaccination planning is still nascent, with no clear timeline. Mass testing, population tracking, and lockdowns seem to be the preferred strategy. Beijing imposed a lockdown of 1.7 million people in part of the Chinese capital with only 15 cases.

At least 2 billion doses are needed to bring the virus to a halt in China. Sinopharm and Sinovac only have enough manufacturing capacity for 1.6 billion doses, which is not to say 1.6 billion doses will be made this year. Meanwhile, 400 million doses have been promised to other countries. While there are 18 other third-party vaccine manufacturers preparing to produce the Sinopharm vaccine, their capacity is unknown.

We believe China will never come close to achieving mass immunization against Covid-19. Seasonal uptake of flu vaccines is below 3 percent, compared to 60 to 70 percent for advanced economies.

Trust in immunization programs is low. In 2018, when unqualified DTP vaccines were given to children, public dissent was nationwide. For Beijing, social order is paramount.

Before China and the rest of the world reaches significant global immunity, we will live through a dismaying cycle as infections subside and surge—for years. We have not yet touched the high-water mark. Most of the world—including 90 percent of America—remains susceptible to Covid-19.

The following chart shows the share of the total population that has been fully vaccinated.

Source: Our World in Data

This brings us to some key observations:

Of the seven known human coronaviruses, four circulate widely and cause up to a third of common colds and, on rare occasions, pneumonia and even death. We believe that Covid-19 is the fifth endemic coronavirus—meaning slow, sustained transmission will persist, becoming less deadly as time goes on.

The pandemic won’t end this year or next year. Even if the pandemic is curbed in one part of the world, it will likely continue in other places. If immunity last less than a year, a span in line with other human coronaviruses, there could be annual surges in infections until more people develop immunity through exposure and vaccination.

Precautions like mandating masks, imposing quarantines, working remotely, and restricting travel are going to continue longer than is widely perceived. As long as the virus persists somewhere in the world, the threat of new local outbreaks, and a return to lockdown, will remain.

The pandemic ushered in a more a digitally native life, accelerating a bunch of trends—online shopping, digital payments, telehealth, remote work, distance learning, virtual experiences and so on. It’s possible our living habits have changed forever. Technologies for shopping, working, learning and socializing remotely will only get better.

The pandemic will last long enough to change capitalism and free enterprise. Governments will prioritize human outcomes over budget outcomes and revise the social contract. This means massive fiscal spending to support the economy, some form of basic income, and higher wages and taxes.

An enduring pandemic will result in a bullish policy mix. The Fed will remain accommodative, as employment levels may not fully recover this decade. Inflation also responds slowly to economic conditions in the post-pandemic period. The Fed won’t deviate from their primary objective to address overly exuberant financial markets.

We recommend owning “essential” businesses—those which you can’t imagine life without in a pandemic, such as Amazon, Walmart, Netflix or Disney, DoorDash and Zoom. Stay clear of airlines, hotels, and cruise operators. We might expect a major corporate bankruptcy among them before the end of the pandemic—if it can even be said to end at a discrete point.

In the 1947 novel The Plague, Albert Camus writes, “But what does it mean, the plague? It’s life, that’s all.”

Photo: Shutterstock