“We’ve achieved substantial progress towards our economic objectives,” Jerome Powell said at a Fed policy meeting in May 2013. As then-governor, he advocated reducing the Fed’s monthly bond buying at “the next plausible opportunity.”

The economy was still reeling from the effects of the Great Recession. Inflation was below the central bank’s 2 percent target, and the unemployment rate stood at 7.5 percent. For Black Americans, it was a devastating 13 percent. This was not raised by Powell or any other policymaker during their meeting.

“We’ve got to jump,” Powell told his colleagues. “There is no risk-free path.”

What followed was a minor panic in financial markets, dubbed the “taper tantrum.” Bond yields rose and capital flowed out of emerging markets.

Powell later admitted the taper tantrum “left scars” on him. It was his first full year as a Fed governor. He cites it as one of the reasons why the balance sheet is supposed to be “in the background, gradual and predictable, paint drying” as opposed to an active tool.

Chairing the Fed in a post-pandemic world, Powell now has a different view of what constitutes economic objectives. The Fed wants to get back to a strong labor market that benefits all Americans: blacks, low-wage earners, and those without college degrees. This is a new humanitarian mission.

“We understand that our actions affect communities, families and businesses across the country,” Powell said in March. The US is “a long way” from where it needs to be in terms of employment. He is calling for a “society-wide commitment.”

Source: Getty Images

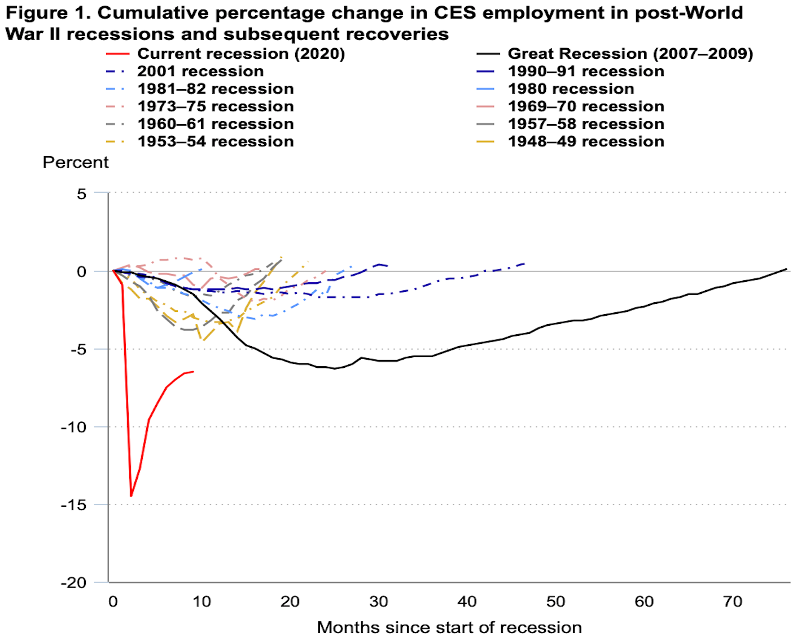

Nonfarm payrolls fell by a combined 22.3 million in March and April 2020. Job recalls drove nearly eleven million people back to work over the summer, but the recalled ranks dwindled after September. We only added two million jobs in the subsequent six months.

Employment bonds between employers and their furloughed workers weakened as time went on. About four in ten unemployed workers have been out of work for more than six months. Many temporary layoffs became permanent. At 3.4 million, permanent job losses are higher today than in December or August.

With speedy vaccinations and businesses reopening, there is hope we can quickly return to full employment. A million jobs have been added in the past two months. We’ve recovered 63 percent of the jobs lost due to the pandemic.

Economists project employers will add jobs at a faster pace than ever seen before on a sustained basis. Goldman Sachs sees a hiring boom with an unemployment rate of 4.1 by year-end and the economy returning to its pre-pandemic payroll level in 2022.

We see it differently.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics

It took 30 months and 48 months, respectively, to regain jobs after the 1990 and 2001 recessions. It took 76 months after the 2008 crisis. It’s taken longer for employment to recover after each downturn, but the pandemic-induced recession was quite different from recessions past.

More typically, job losses in recessions have centered around goods-producing sectors, such as manufacturing and construction. Job losses in the pandemic have been concentrated in service sectors. Of the eight million fewer people employed than in February 2020, less than a million of them work in goods-producing sectors.

Diving into the details, we find there are 3.1 million missing jobs in leisure and hospitality, 1.2 million fewer jobs in education and health, and 685,000 fewer in business and professional services. Another big loss, about 440,000 jobs, sits with the specialty contractors who work on non-residential buildings.

Past recessions disrupted employment from the demand side. Job openings took years to recover. Following the Great Recession, it took 49 months for leisure and hospitality employment to exceed its December 2007 level; 58 months for professional and business services jobs to recover; and 88 months for the retail sector to reclaim its employment peak.

What’s different this time is that the available jobs, some 7.4 million, have already exceeded the pre-pandemic levels. The supply of labor is what’s responding slowly because of health concerns, family demands, and government policies.

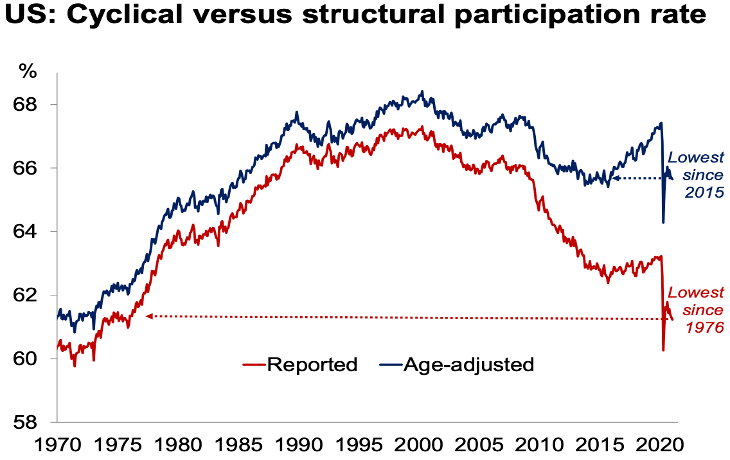

So the key is how quickly labor force participation will rebound. At 61.7 percent, the last time it was this low was 1976. Adjusted for aging, the same metric is at its lowest level since 2015, or 1.8 percent below its pre-pandemic level.

Source: Oxford Economics

The pandemic can do lasting harm to labor supply.

There is widespread consensus among scientists and public health experts that the herd immunity threshold is not attainable. As we wrote in January, the virus will most likely become a manageable threat that will continue to circulate for years to come, causing hospitalizations and deaths but in much smaller numbers.

This prevents a full recovery for the leisure and hospitality sector, which is critical to restoring the jobs market to its former strength. Even with 1.8 million restaurant workers displaced by the recession, restaurants are struggling to ramp back up because they can’t recruit enough employees. The pandemic has made hospitality occupations less attractive.

Some people aren’t actively looking for work due in part to the enhanced unemployment benefits available until September (for a maximum of nearly eighteen months). Those qualifying for the $300 weekly enhancement are earning the equivalent of working full-time at $15.50 an hour. That’s distorting labor supply.

Two-thirds of unemployed workers have received benefits which exceeded lost earnings. One-fifth may have received benefits at least double lost earnings.

Prime-age labor force participation (25- to 54-year-olds) was the highest in over a decade in February 2020, at 83 percent. Now it’s 81.3 percent. Those without college degrees have seen their participation rate decline from 58.3 percent to 55.4 percent. Since 1967, hours and earnings for men without a college education have fallen sharply during recessions and failed to fully recover during subsequent expansions.

The employment-to-population ratio, measuring the proportion of the working-age population that is employed, is nearly 7 percentage points short of its peak reading of 64.7 percent in April 2000 and more than 3 points below where it was before the pandemic began. For Black Americans, it is 55.3 percent compared to 59.3 percent in February 2020.

These three categories, Black unemployment, labor force participation for those without college degrees, and wage growth for low-wage workers, are important to the Fed’s new mission, and each has historically taken longer to recover from downturns than broader metrics. The corollary is that it will take years for the Fed to meet their broad-based and inclusive employment goals.

Source: Reuters

One of the pandemic’s enduring consequences could be older workers retiring earlier than expected. Oxford Economics estimates that around two million workers have retired from the labor force since the start of the pandemic, more than twice 2019’s departures. Participation among workers aged 55 and over is lower than at the worst point of the recession.

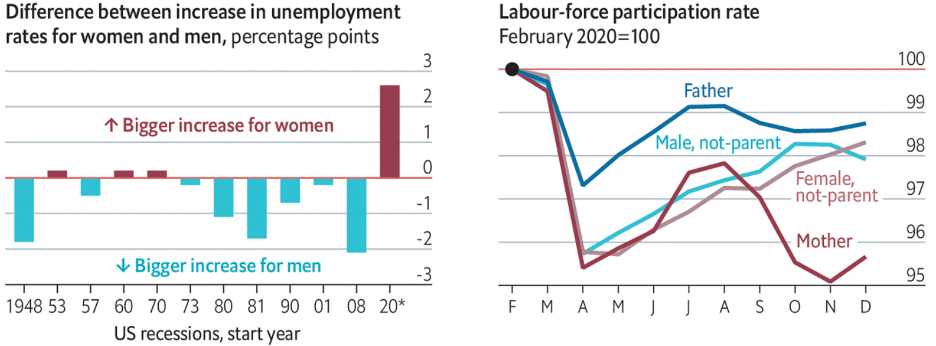

The pandemic has inflicted disproportionate damage on sectors that intensively employ women, such as retail stores, restaurants, and hospitality businesses. These part-time, temporary, and contract jobs eliminated during the downturn were largely held by women. Their participation has not been this low since 1987. Women with children, particularly Black women and those without a bachelor’s degree, faced the sharpest decline.

The labor force participation of mothers dropped by 4 percent, and their employment rate dropped 7 percent. A study from the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis found that that the effect was biggest for mothers with children under five. Women’s participation is closely tied to access to childcare, which is disrupted by the pandemic.

Researchers at the Bureau of Labor Statistics worry that, just as some older manufacturing workers lost jobs in the Great Recession and eventually stopped looking for work, considering themselves “retired,” many mothers with young children who lost jobs may now consider themselves “homemakers.”

Both parents work in two-thirds of families in which married parents have children. The majority of America’s 13.6 million single parents also work. Women in their prime working years have quit the labor force at nearly twice the rate of men. Childcare challenges have become a major barrier to work.

Vice President Kamala Harris has called the exodus of women from the workforce a “national emergency.” Neglecting to fully apply the talents of half the population will see the U.S. economy operating below its full potential.

Source: The Economist

So, what do we make of it all?

Our observation about the constrained supply side of the labor market aligns with a generally dovish monetary policy stance over the coming years. This is not good for the dollar.

Hitherto, the Fed tightened monetary policy as employment rose toward its estimated maximum level to stave off an unwelcome rise in inflation. (At the onset of the last Fed rate hike cycle in December 2015, the unemployment rate for Blacks was still an achingly high 9.4 percent). But now the Fed’s policy decision will be informed by their “assessments of the shortfalls of employment from its maximum level.”

What this means is that the Fed will not tighten monetary policy solely in response to a strong labor market. Under the compulsions of a new cultural milieu, which reflects growing recognition of systemic injustice, the Fed has come to believe that it can assure gainful employment for every willing hand.

Employment can run at or above real-time estimates of its maximum level without causing any concern, unless of course there’s unwanted increases in inflation. (Last month, we explained why inflation will remain contained despite near-term risks to the upside.)

The problem with the Fed’s policy twist is that all these pandemic-induced changes in the social and economic environment make it difficult to know what the natural unemployment rate (u*) is corresponding to full employment.

Most estimates suggest that u* has declined since the 1980s and is somewhere around 4 percent. But what if the level of u* is higher now, driven by changes in labor laws, generous unemployment benefits, early retirement, and rising minimum wages? Workers are pickier about taking jobs.

In waiting for all the people who left the labor force in 2020 to return to work, the Fed may have set itself an unachievable target. No one can know for sure at what point we have reached maximum employment.

The decline in the unemployment rate depends on the recovery in the labor force participation rate. More than four million people have quit the labor force since the pandemic began. Strong jobs growth over the summer will encourage many of these workers to return. This upswell in the unemployed ranks will lead to a slower decline in the unemployment rate than what the consensus expects. We believe the US economy will not return to its pre-pandemic payroll level or unemployment rate by 2022.

Going by our inflation and employment outlook, one may think that the Fed can refrain from shifting its monetary policy for a long time to come. While short rates will remain near zero to continue to support the economy, we believe the Fed will still have to reduce its monthly bond purchases.

The US deficit for fiscal 2021 will come to $3.4 trillion and $1.6 trillion for 2022. Current bond purchases amount to more than $1.4 trillion a year. The Fed will taper in late 2022 simply because government funding needs will scale back significantly. The Fed’s balance sheet is more of a budget management tool.

Investors are increasingly divided on the wisdom of Fed policy. Our view is that tapering won’t be harmful because the Fed, even next year, will remain far from achieving its inflation and employment goals. Powell will err on the side of caution and accommodation so long as conditions of social discrimination and economic deprivation persist.

A bigger risk is the constant stream of headlines about labor supply being unable to meet demand across a host of sectors. This will lift wages, dampen potential growth, and prevent the economy from running hot. The gains generated by more women entering the workforce are reversing, and the growth in the working-age population (or labor force growth) is slowing.

The fate of the business cycle—and the bull market—depends on the direction of productivity. Rising productivity leverages job creation, allowing wages and profits to rise simultaneously, and it boosts supply to meet rising demand, which mitigates cyclical inflation and interest rate pressures. We are optimistic about a new era of productivity-led growth, like the early 1950s, 1960s, or late 1990s.

Over long periods, the only road toward higher prosperity is paved by productivity gains.

Source: Reuters