Each bull market has its own “structure of feeling,” as the cultural theorist Raymond Williams put it. When we think about the future, we try to imagine how that feeling might change. How will we feel when new information emerges? What should we do if something unexpected happens? Orienting ourselves is a thought experiment.

Right now, things feel rosy, but what can the sixties tell us about how we should be thinking now? Sifting history’s sands will take us only so far, but there’s still wisdom in those hills.

In 1961, the Dow Jones gained 19 percent, reaching a high just short of 735. Volume on the Big Board totaled over a billion shares, more than any year since 1929. The market was feeling young President John F. Kennedy’s go-ahead spirit. People believed this was the time for action, progress, and wonderful things, whatever they were.

The economy was in a rapid expansion, but without warning the stock market began a gradual decline as the year turned. On May 28, 1962, the day that Wall Street annals deem Blue Monday, stocks “broke.” The Dow average dropped 5.7 percent, a one-day collapse second in history only to that of October 28, 1929, when the loss had been 12.8 percent.

From The New York Times archives:

Principals were mercilessly sacrificed by their brokers, margins wiped out, contracts repudiated, abusive epithets lustily interchanged, much to the entertainment of disinterested and patriotic spectators of “the slaughter of the innocents.” At the close of the day’s festivities lame ducks were a drug in the market, and the erstwhile much envied stock gamblers could find none so poor as to do them reverence. They have sowed the wind and have reaped the whirlwind.

Source: The New York Times

The Dow fell about 23 percent in six months. Shares of IBM “crashed like a boulder pushed from a cliff,” from $607 to $355. On June 19, the New York Herald Tribune wrote that “the experts have been confounded and there’s not an unshattered crystal ball left in Washington.” Investors bombarded the White House with complaints and pleas for help.

Oil tycoon J.P. Getty addressed the press: “When some folks see others selling, they automatically follow suit. I do the reverse—and buy. I don’t think the slide will go on.”

With the backing of successful investors, the public’s fears subsided. The Dow bottomed on June 25 at 561 and recovered its prior peak fourteen months later. In 1963, volume on the Big Board hit all-time highs, topping even 1929. The go-go years had begun.

In The Go-Go Years: When Prices Went Topless, John Brooks writes:

The term “go-go” came to designate a method of operating in the stock market—a method that was, to be sure, free, fast, and lively, and certainly in some cases attended by joy, merriment, and hubbub. The method was characterized by rapid in-and-out trading of huge blocks of stock, with an eye to large profits taken very quickly, and the term was used specifically to apply to the operation of certain mutual funds, none of which had previously operated in anything like such a free, fast, or lively manner.

“We didn’t want to feel that we were married to a stock when we bought it,” said Edward Crosby Johnson II, the founder of Fidelity Investments. Johnson preferred to think of the investor-stock relationship as “companionate marriage.” He might have enjoyed a “liaison” now and then, or even “a couple of nights together” on rare occasions.

Investing decisions were calling for the speed, dexterity, and intuition of a single man operating alone rather than the committees used by typical money managers. The old Wall Street star system, in vogue before 1929 but absent for a generation, was making a comeback. The portfolio managers running mutual funds were the new stars.

What grace, what timing

Gerald Tsai was not yet 30 when he started Fidelity Investments’ first aggressive growth fund in 1957. From the beginning he ran the fund like he was gambling: swiftly moving money from here to there, pouring into hot growth stocks that were considered outrageously speculative for a mutual fund. Annual portfolio turnover exceeded 100 percent—virtually unheard of at the time.

“It was a beautiful thing to watch his reactions,” Johnson said. “What grace, what timing—glorious!” Tsai earned a well-deserved reputation for his accuracy in predicting market turns. “Gerald Tsai,” wrote Newsweek, “radiates total cool.”

In the twenties Jesse Livermore was the guy to whom the public credited nearly magical capacity to predict future stock values. In the sixties, more than any other man, it was Gerald Tsai. His prophecies, like Livermore’s, became somewhat self-fulfilling because of his fame. He was the star of the bull market. “Gerry Tsai is buying it!” became the signal for a stampede.

Source: The New York Times

Tsai’s wild success spurred the creation of “performance funds,” which had sports-like appeal. The results were measurable in numbers, so if a manager’s portfolio increased by 30 or 50 percent, he (and it was always he in those days) was a clear winner, acknowledged and paid accordingly. Was he liked by his coworkers? Did he have the proper pedigree? It didn’t matter. As in sports, the winner became an instant celebrity.

Brooks again:

In the new climate, an under-thirty had so much going for him that he sometimes needed to pick only a single stock-market winner to become nationally famous. It was coming to be believed, in the absence of evidence to the contrary, that almost any man under forty could intuitively understand and foresee the growth of young, fast-moving, unconventional companies better than almost anyone over forty ... only the young were equipped to understand and master the new world.

The buzz on Wall Street

On June 1, 1965, Fed chairman William McChesney Martin, Jr. identified “disquieting similarities between our present prosperity and the fabulous Twenties,” implying that his era’s boom might end as painfully as the one before. Stock prices plummeted as a result of his comments, which were interpreted as a hint of further monetary tightening.

The average investor was “perplexed but not panicky,” the New York Times reported. While there was some concern about how long the business boom would last, once stocks actually started to decline, “the chart boys saw sell signals and the decline began feeding on itself.” In the next three weeks the Dow dropped to its lowest level in nearly a year.

Wall Street began talking of the “Martin market,” which turned around swiftly and kept charging upward the rest of the year, passing the old Dow record of 940 in October. It was the busiest week in history up to then with almost 45 million shares changing hands. (The previous record was set in the fateful final week of October 1929.)

That magnificent autumn on Wall Street, the buzz was of 1,000 on the Dow—that, and the great new force in the market, mutual funds, which accounted for a quarter of all trading. With such momentum, the magical 1,000 was within easy reach, and published on every financial page.

By this time, Brooks explains, Wall Street grudgingly began to see itself as a marketplace for the masses, rather than an exclusive gambling club with a small membership. New investors and new money were pouring into the market in droves. It was often said that mutual funds were finally making “people’s capitalism” a reality rather than a catchphrase; through fund investing, the small investor could obtain expert advice and quick action that his limited resources would otherwise deny him.

In 1965, twenty-nine leading performance funds made up of glamour stocks like Polaroid and Xerox returned just over 40 percent, while the laggard Dow, with blue chips like AT&T, General Electric, General Motors, and Texaco, had risen only 15 percent. Tsai finished up nearly 50 percent on a turnover of 120 percent and decided to set out on his own.

Seeking to raise $25 million for his new Manhattan Fund, Tsai wound up with ten times that amount, as investors flocked to his fund. “He far underestimated the extent to which he had captured the public imagination,” Brooks writes. It was the biggest offering in investment company history.

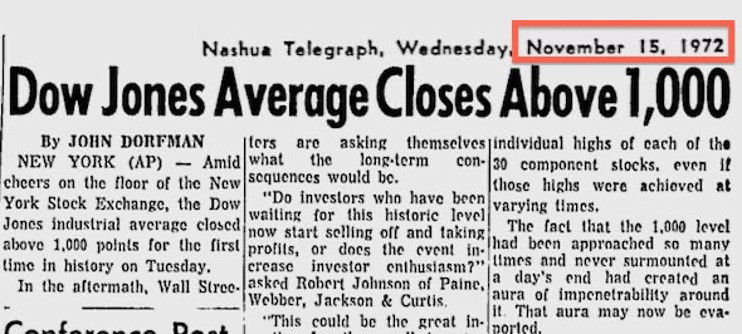

The irony of it all is that Tsai started his fund just a few weeks after the sixties bull market ended. On February 9, 1966, the Dow touched 1,001.11 for a matter of minutes before falling back. As it turned out, that was the peak. It wouldn’t hit 1,000-mark again until 1972.

Tsai rode unwittingly into his demise. He had two middling years and then the fund lost 90 percent of its value.

Source: Nashua Telegraph

The times they are a-changin’

The bear market of 1966, during which the Dow dropped 23 percent to a low of 749, lasted only eight months. It was not followed by a recession; instead, a new speculative binge—the second in the decade—took hold. The average daily trading volume for 1967 on the New York Stock Exchange surpassed ten million shares, a new high by a long shot.

Brooks describes the manic phase of the go-go era:

Nineteen sixty-eight was to be the year when speculation spread like a prairie fire—when the nation, sick and disgusted with itself, seemed to try to drown its guilt in a frenetic quest for quick and easy money.

“The great garbage market,” Richard Jenrette called it—a market in which the “leaders” were neither old blue chips like General Motors and American Telephone nor newer solid stars like Polaroid and Xerox, but stocks with names like Four Seasons Nursing Centers, Kentucky Fried Chicken, United Convalescent Homes, and Applied Logic.

All through the stormy course of 1967 and 1968, when things had been coming apart ... one could only ask: did Wall Street, for all its gutter shrewdness, have the slightest idea what was really going on?

Obviously not.

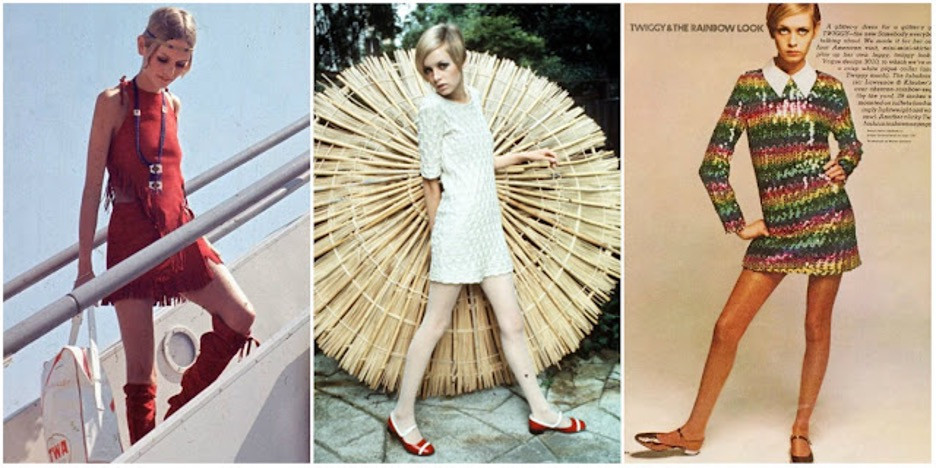

In May 1967, the brokerage firm Harris Upham published research showing that the stock market and the hemlines of women’s skirts move in the same direction. “From the days of street-sweeping skirts in 1897 to the days of Twiggy in 1967, the market was up 2,100 percent,” the analyst wrote, concluding: “Perhaps we should be listening more carefully to the planning in Paris.”

Source: Vintage

The Merger King

The low interest rates and high valuations of the era triggered a conglomerate boom. Mostly one- or two-man operations, the conglomerates were a means by which “ruthless capitalists practice the black arts of finance to their ends”; or a kind of business that “services industry the way Bonnie and Clyde serviced banks.”

A fast-growing business with a high valuation multiple would use its shares to buy low-growth firms, with the merged company’s earnings having the same multiple as the fast-growing company. This allowed conglomerates to take unprecedented hold of diverse industries. All that was needed was to have a “story”—a simple notion that sounded profitable and was preferably connected to a major trend.

The president of a middle-sized firm with conglomerate aspirations asked a broker to identify for acquisition “some kind of company that would be located in Florida” because he liked the climate and needed a reason to visit. It was an era of “showoffs and shenanigans,” according to Brooks, when American business mocked itself on a big scale. Most of the 150 monthly mergers taking place by the late sixties were executed by conglomerates.

James Ling’s dazzling financial acrobatics made him one of the early pioneers in the conglomerate merger wave. “He collected companies the way boys collect baseball cards,” the New York Times reported as he built the country’s fourteenth-biggest company, Ling-Temco-Vought (LTV), in just fourteen years.

“Acquisitions must meet the test of the 2 plus 2 equals 5 (or 6) formula,” Ling stated in LTV’s 1966 annual report. His conglomerate ran more than eleven corporate subsidiaries that offered 15,000 separate products—from hamburgers to missiles, from tennis rackets to consumer electronics.

At the height of the era, Newsweek hailed Ling as the ”Merger King.” Another magazine pronounced that “it is theoretically possible for the entire United States to become one vast conglomerate presided over by Mr. James Ling.”

Source: Newsweek and Esquire

Gunslingers and the people’s capitalism

From the October 1966 bottom to the December 1968 top at 985, the Dow rose 31 percent. “The bull market,” writes Brooks, “in the classic way of bull markets, had begun to lead a happy and profitable life of its own, independent of underlying reality.”

Brooks again:

Hardly anything on Wall Street had remained the same since 1965. The most conspicuous change was the triumph of youth. The battle of the generations had ended in a rout; living out the Freudian fantasy, Wall Street by now had killed its father. The late sixties became, for a shockingly brief moment, the heyday of the young prodigy, the sideburned gunslinger.

A Boston firm calculated that only a shocking 10 percent of all investment professionals were forty-five years old or older. “In plain numbers,” Brooks writes, “youth had taken over Wall Street.” These young hotshots tossed around the latest clichés: “performance,” “concept,” “innovative,” and “synergy.”

The average investor of the sixties was a novice, interested in little more than the price-to-earnings multiple as a yardstick to judge whether a stock was a bargain or not. “Making this calculation,” notes Brooks, “marked the outer limit of his investment sophistication.”

Merrill Lynch opened over two hundred thousand new brokerage accounts in the first five months of 1968. Stock investment had become a “milieu for the millions.” There were now thirty-one million Americans who owned a stock, more than one in every four adults, a 53 percent increase since 1965 when there were just over twenty million.

In other words, approximately eleven million Americans made their first stock purchase between 1965, when the Dow was just under 1,000, and 1970, when it was around 650. “People’s capitalism had left one-third of all American investors poorer than it had found them,” laments Brooks. The paper loss in the 1969—70 crash was $300 billion.

Go-go back down to earth

As the go-go years were ending, President Johnson’s policies had produced a sharp rise in deficit spending; the unemployment rate fell below 4 percent, and inflation was on the rise, after languishing under 2 percent for a long time. The Fed aggressively raised rates, inverted the yield curve, and a mild recession followed. The stock market went into a “sickening collapse.”

The Dow, after peaking at 985 in December 1968—only a few points below the all-time high of February 1966—declined 35 percent by May 1970, erasing all the gains from the go-go years. Bonds suffered losses even as stocks stumbled because of a structural rise in inflation expectations.

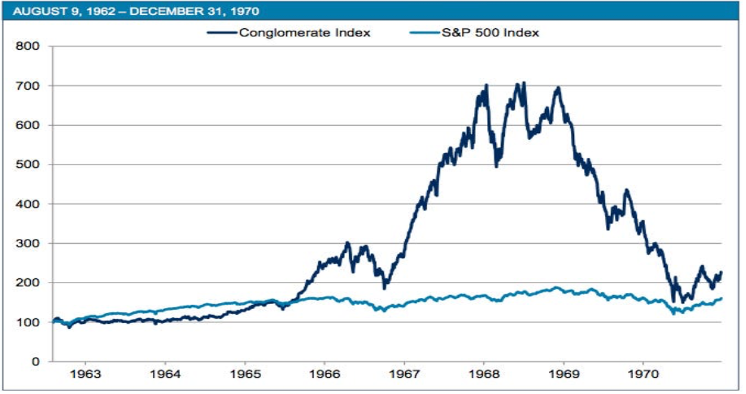

Many of the gunslingers who had touted the highfliers of the market were fired or left the securities business. Computer-leasing stocks were down 80 percent. The conglomerates crashed to the tune of 86 percent. LTV’s stock, which traded for as much as $169 a share in 1967, plunged to a low of $4.25 in 1970, when Ling was ousted.

The assets of the twenty-eight largest hedge funds declined by 70 percent, or about $750 million. “The dumb money,” Brooks writes, “could take bitter comfort in the company it had among the smartest of the smart money.” According to a study, an equally weighted investment in stocks would have yielded a higher return than mutual funds for the 1960—1968 period.

Source: JHL Capital

The triumph (and folly) of youth

So what lessons do the go-go sixties hold for our YOLO years?

(1) In the twenties the “great new force” were the pool operators; in the sixties they were the portfolio managers; now they are the retail traders. Around 59 million people held accounts with one of the top seven American brokers in 2019. Today that number is 96 million, a 63 percent increase, with 17 million new accounts created in 2020 and 20 million already created this year.

Retail investors poured $141 billion into the US stock market in the first half of this year. That is up more than 30 percent from the same period a year ago, and more than six times the amount during the same stretch in 2019. Retail trading went from around a quarter of volumes to a third in early 2020 and peaked at over 40 percent in the first quarter of 2021.

Once again, we are seeing the “triumph of youth.” The average Robinhood user is 31 years old. The trading app has 31 million total accounts, with 18 million of those being funded. The r/WallStreetBets forum on Reddit, which drove up the price of GameStop shares and produced large losses for hedge funds, now boasts 10.8 million members—or “degenerates”, as they call themselves. This is “people’s capitalism.”

The naivete of millions of new investors was the crucial element in the final go-go years. These days stockholdings among US households stand at 41 percent of their total financial assets, the highest level on record.

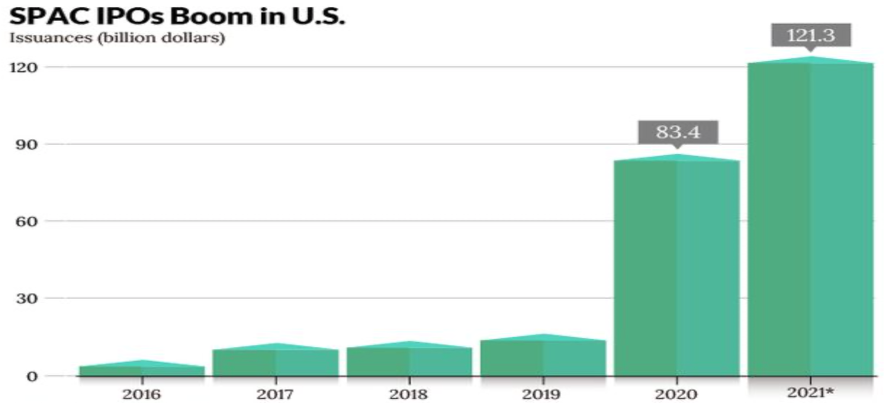

(2) Investment trusts and holdings companies became wildly popular with investors in the twenties; it was conglomerates in the sixties; now SPACs have unleashed an era of “showoffs and shenanigans.”

So far this year, 435 SPACs have raised nearly $126 billion, according to SPAC Research. That’s a huge jump from prior years: in 2020, 248 SPACs raised over $83 billion, and in 2019, 59 SPACS raised more than $13 billion.

We should see a frenzy of deal activity next year as the two-year clock to seal a deal is ticking away. According to research by Renaissance Capital, two-thirds of SPACs that went public in 2021 are trading below their offer price, with most of them having yet to identify a merger target.

As Brooks reminds us, “Wall Street nearly committed suicide by swallowing too much business, and by compounding its own near-fatal folly by simultaneously encouraging more of the same.”

Source: SPAC Research

(3) In 2014, Cathie Wood followed her spiritual calling and launched Ark Invest. In prayer and meditation, she was hit with the epiphany: “You cannot worship any idol, and the benchmark has become an idol.” Her slate of actively managed ETFs leveraged her zealous belief in transformative technologies that were going to change the world.

Woods is the “star” of this bull market. As the pandemic took hold, she moved stocks with her trades and her tweets, acquiring nicknames like “Money Tree,” “The Godmother,” and “Mama Cathie.” Bloomberg dubbed her “The Believer” when some of her bold predictions for bitcoin and Tesla came true, much to the shock of Wall Street analysts.

From its March 2020 low to its February 2021 peak, her flagship ARK Innovation fund (ARKK) jumped more than 350 percent. Assets rose more than tenfold to $25 billion. Firm-wide assets are now $85 billion, from less than $10 billion at the start of 2020. Her wild success has inspired large asset managers to launch their own gimmicky themed ETFs.

ARKK has delivered an annualized return of 35 percent over the past five years, nearly triple that of the S&P 500. Most funds tracked by Morningstar that gain as much over a similar time frame have seen returns subsequently cool or even turn negative. This year ARKK is down about 3 percent, while the Nasdaq is up roughly 17 percent and the S&P 500 about 21 percent.

“Keep the faith,” she tells her legion of YOLOing fans. “Innovation is on sale.” She expects the stocks in her portfolios to more than triple in the next five years. And bitcoin? She believes it could hit $500,000 and replace bonds in the traditional 60/40 stock—bond portfolio.

We can’t help but think that, like Gerry Tsai before her, Wood’s star is about to wane. What if the hyper-sensitive risk assets, such as ARKK and SPACs have already peaked for the cycle?

New stock market highs combined with lower highs in these assets will help confirm that the underlying risk picture is less promising.

Source: The New York Times

(4) With all the drama and hoopla surrounding the go-go years, it’s worth remembering that the first speculative binge, from 1962 to 1966, lasted four years and saw the Dow rise by 80 percent. The Dow then went on a two-year speculative frenzy that saw it rise 31 percent to its 1968 summit (which was still beneath the 1966 high).

By comparison, the Dow has nearly doubled in just eighteen months post-pandemic. Everything is happening at a quickened pace.

The top of the stock market will come “without warning.” But first, 40,000 on the Dow (and 5,000 on the S&P 500) is the “magic number” within easy reach. It is not yet mentioned on every financial page, which suggests the “structure of feeling” may turn more ebullient before the bull market ends.

According to Deutsche Bank’s survey of market professionals, 58 percent of respondents said they expected the stock market to fall by 5 to 10 percent by the end of the year. Another 10 percent said the market would fall by more than 10 percent. This does not evoke euphoria. The S&P 500’s average stock is down 10 percent from its 52-week high. In the Russell 2000, 55 percent of stocks are down at least 20 percent from their 52-week highs.

We remain confidently bullish. The key insight from financial history we shared last year was that the pandemic is more than just our century’s defining global health and economic crisis. The pandemic is a major “displacement.”

A cursory reading of Charles Kindleberger’s Manias, Panics, and Crashes shows that every speculative mania starts with just such a displacement, some exogenous shock that introduces lasting change to the macroeconomy.

Displacement in the 1920s comprised the mass adoption of automobiles, the development of highways, electrification of much of the country, and the beginning of radio. The collapse of the Bretton Woods system was a displacement that led to the 1970s gold mania. In the 1990s it was an information-technology revolution leading to the dot-com bubble. China’s entry into the World Trade Organization in 2001 was another displacement, which led to the bubble in commodities.

The pandemic reordered society in dramatic fashion—accelerating technological adoption and driving changes in consumer and business behavior that will have long-lasting effects. We maintained now that we’ve endured the “displacement,” we’ll enter the boom phase as per Kindleberger’s framework. The euphoria stage lies well ahead.

After a year of runaway home and stock prices, the future is here. The period of seasonal weakness for stocks ends shortly, when we suspect the greed itch will evolve into a state of euphoria. Is there anything worse than giving up too soon and leaving money on the table? HODL!