Markets are a tiny facet of society, but because they are molded by mass psychology, they are a good barometer. They only function when people have faith in them, and this faith is based on the belief that leadership knows what it’s doing and can govern wisely. “If that belief fades,” wrote George Goodman in The Money Game, “then so do the markets. They do not merely dive; they dive and then they disappear.”

Almost half of credit investors polled by Bank of America indicated that a Fed policy mistake is their biggest fear. Investors believe that entrenched inflation will put an end to the era of central bank predictability, with upcoming rate hikes being quicker, greater, and more chaotic than in the past.

Does the Fed know what it’s doing?

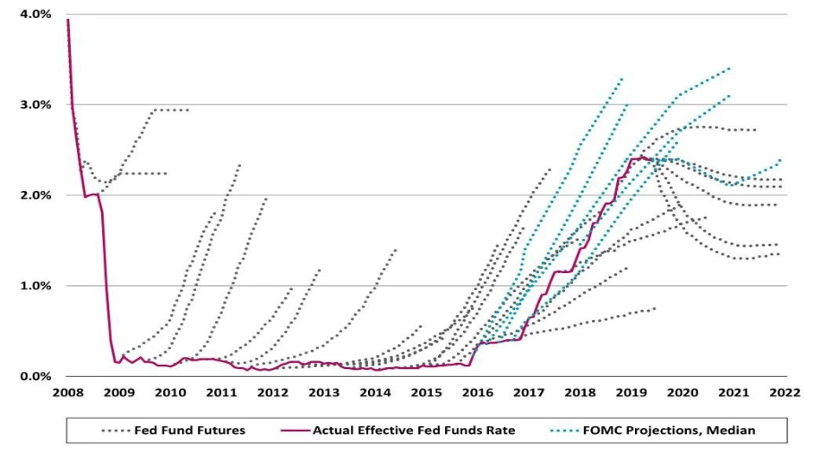

After projecting three quarter-percentage-point rate rises this year, most Fed officials have penciled in at least three more rate increases in 2023 and two more in 2024. Fed Funds futures have essentially locked in a rate hike at the March meeting and priced in four rate hikes through 2022. Fed chair Jerome Powell said the Fed will stop buying assets in March, as planned, and could start to shrink its balance sheet later this year.

Policymaking in view of the world necessitates a certain practical humility. The market is almost always wrong about what the Fed will do. And it turns out, the Fed’s own best guesses, the so-called “dot-plot,” isn’t much better.

Source: Blackstone

It’s worth revisiting the last Fed tightening campaign. In March 2014, then Fed chair Janet Yellen said that the first interest rate hike could come “something on the order of around six months” after QE was to end in October 2014. Four Fed officials thought rates could be at 1 percent at the end of 2015. Instead, the Fed only hiked rates once in December 2015.

The decision to lift interest rates from near zero after seven years of holding them there was approved unanimously. Inflation was still running below the Fed’s 2 percent target; officials, however, projected that falling unemployment would eventually firm up prices.

“There’s not a slam-dunk case for tightening at this meeting,” said William Dudley, then the president of the New York Fed. He worried about the weakness in emerging economies and the impact of a stronger dollar. Fed governor Lael Brainard said the risk of slower growth abroad “leads me to place somewhat greater weight on the possible regret associated with tightening too early than on the possible regret associated with waiting a little longer to see some of these risks play out.”

After just 10 trading days in January 2016, global equity markets had lost more than $4 trillion of value. Sliding oil prices and lingering worries about the global economy offset upbeat US job growth, prompting the Fed to delay anticipated rate increases until December.

The Fed lifted rates three times in 2017 and started gradually shrinking its balance sheet. The S&P 500 returned 18 percent. A growing number of officials now believed rates could be 2 percent or higher. Four rate increases in 2018 brought the fed funds rate to 2.5 percent. But market turmoil led Fed chief Powell to signal an end to rate increases in early 2019.

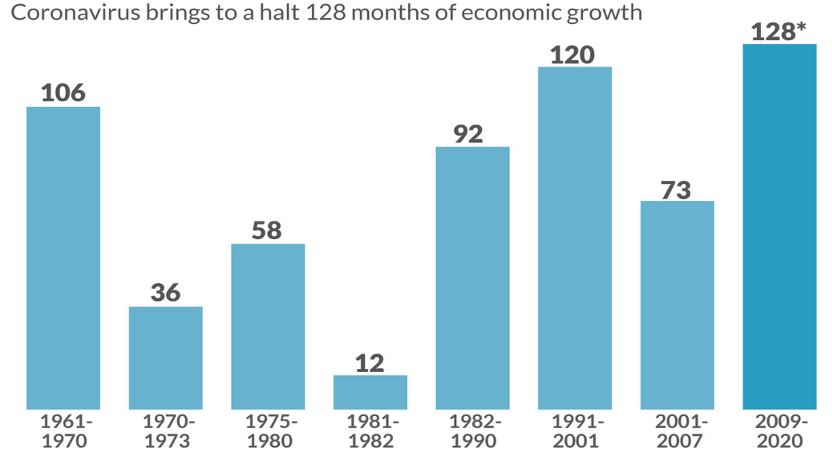

The Fed’s tightening cycle was fraught with uncertainty, and the timeline kept shifting, yet the US ended up with the longest economic expansion and bull market in history.

Source: NBER

Since we’ve only had one rate-hike cycle in the last fifteen years, it’s easy to forget how markets adapt to monetary tightening.

Two things happen: (1) the forward price-to-earnings (PE) multiple compresses so the S&P 500 falls about 10 percent, and (2) the yield curve flattens to a 100 basis points spread between the 2-year US Treasury bond yield and the 10-year yield within two months of the initial rate hike.

The S&P 500 is down 10 percent, the Nasdaq is down 15 percent, and the Russell 2000 is down 20 percent. The spread differential between the 2-year and 10-year rates has collapsed from nearly 160 basis points in March to 75 basis points. This is what’s going on: financial markets are simply adjusting to a new rate hike cycle. That is all there is to it. There’s nothing else to be concerned about.

In fact, due to the Fed’s considerable telegraphing of its plans, the adjustment is occurring faster and more forcefully than in the past, and it may be practically complete even before liftoff. We think the equity market selloff has run its course.

The investment climate is shifting away from an over-reliance on liquidity and toward growth. These transitions are usually challenging, and this one is made even more difficult by the fact that the pandemic has distorted growth and inflation perspectives as well as the overall macro picture.

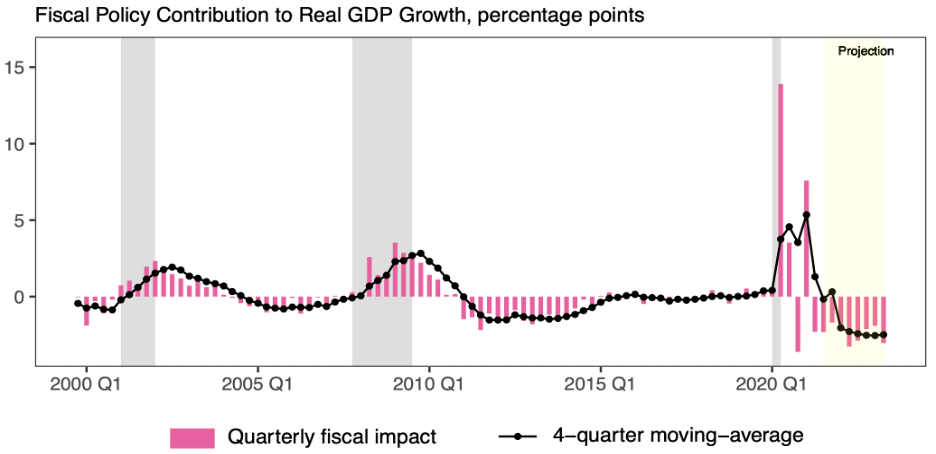

After a strong rebound in 2021, the US economy will decelerate this year. However, 3 percent real GDP growth is still healthy and above-trend. The federal deficit will shrink from 13 percent of GDP to 5 percent in 2022, subtracting from GDP growth. But let’s not forget that the fiscal impact was negative throughout the previous decade. Most households are financially better off now than before the pandemic. Moody’s Analytics estimated that there was still $2.5 trillion left in excess savings as of October and that the total would decrease by $50 billion a month on average through the end of 2022.

Wages are rising, savings rates are falling, and with banks loan growth set to accelerate, we believe the withdrawal of central bank liquidity is likely to prove less disruptive than what is typically experienced during the late-cycle tightening of monetary policy. With investor skepticism still high, the market’s bullish potential remains intact.

Source: The Hutchins Center

The stock market’s bull run from the pandemic lows can be divided into three stages.

The first phase (March to September 2020) was a policy-induced rally. The combined fiscal and monetary actions were unprecedented, with the global stimulus tally exceeding $20 trillion. The S&P 500 forward PE multiple jumped from 13 at the March lows to over 23, or 76 percent, offsetting a 12 percent drop in earnings for the 2020 calendar year. The S&P 500 gained 64 percent to reach its September high before falling 11 percent.

The second phase (September 2020 to December 2021) was a low-conviction rally. The pandemic was still spreading around the world, and wage inflation and supply chain bottlenecks were becoming more of a problem. The strength of corporate earnings, which increased by 54 percent, surprised many and compensated for the multiple compression. The S&P 500 rallied 50 percent during this phase, peaked on January 4, and has since corrected 10 percent.

Looking ahead, we believe the bull market will soon enter its third and perhaps final stage. This will be a high-conviction rally based on receding macro fears and rising economic optimism. On average, US stocks gain 35 percent during this phase (the average returns based on five previous “third phases” of a bull market between 1974 and 2020), driven by a mix of earnings growth and multiple expansion.

Because the global economic expansion is often becoming self-reinforcing and broadening to include more countries, non-US markets tend to outperform. Year-to-date, we’ve seen this unfurl. While value stocks are outpacing growth stocks, the latter eventually reclaims the lead. And EM carry trades make a comeback as risk appetite increases.

In perhaps the most famous scene of J. M. Barrie’s 1904 stage play Peter Pan, Tinkerbell, dying after swallowing poisoned medicine meant for Peter, tells him that she believes she could get better if children believed in fairies.

“Say quickly that you believe!” Peter implores the youngsters in the audience at this point. “Clap your hands if you believe!” Thanks to them, Tinkerbell is rescued, and Peter goes off to the play’s last struggle to save Wendy.

The bull market appears to be dying, but the secret to its survival has been its ability to withstand a chronic wall of worry. Do you believe in the Fed? Clap your hands if you believe.