We have found it useful to study the Nifty Fifty period and the 1973—1974 bear market as it appears to have considerable overlap with the so-called FAANG stocks: Facebook, Amazon, Apple, Netflix, and Google parent Alphabet.

The Nifty Fifty were a group of premier growth stocks such as Xerox, IBM, Polaroid, McDonald’s, Disney, Pfizer, Merck, Procter & Gamble, Pepsi, and Coca-Cola that became institutional darlings in the early 1970s. They sparked a radical shift away from value investing.

At their peak in 1972, the Nifty Fifty traded at 42 times earnings, more than twice the S&P 500’s lofty average of 19. Investors were willing to pay a steep premium because these companies were generating rapid earnings growth and had quality franchises, which, it was believed, would earn them high returns on capital well into the future.

While this speculation was proven correct—average annual earnings growth was 11 percent through 1996—the delusion was that it didn’t matter what you paid for them. A great company is not the same thing as a great stock, and caution was in order.

The Nifty Fifty were considered “one-decision” stocks, to be bought and held for life. That worked out just fine for a buy-and-hold investor, as a portfolio of Nifty Fifty stocks purchased at the peak would still have matched the S&P 500 return over the next 25 years at 13 percent annually, but first they would have had to withstand a grueling decline.

Source: Investor’s Business Daily

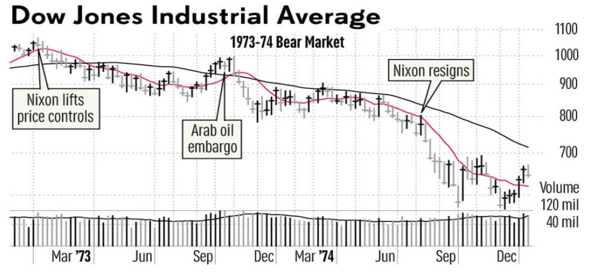

The Dow Jones Industrial Average had a good year in 1972, up 15 percent, but its advance was narrowing. The Nifty Fifty stocks powered ahead while other smaller issues languished. On January 11, 1973, the Dow rose to an all-time high of 1067.

Barron’s article titled “Not a Bear Among Them” captured the sentiment. L.O. Hooper of the brokerage W.E. Hutton & Co said, “The economy is becoming less and less vulnerable to big booms and big busts.” On January 23, President Nixon announced the end of the Vietnam war.

The Dow’s initial move down from the January high was very sharp, and within a month it was off 100 points or almost 10 percent. The rise in inflation and interest rates started to hurt the economy and Nifty Fifty stocks. The Watergate scandal was also widening as top Nixon aides resigned at the end of April on charges of obstruction of justice.

The Dow’s fall continued until late August into bear market territory when it finally bottomed at 857. Over three hundred public stock offerings were withdrawn. “The stream of equity capital to US industry has run dry,” Business Week reported.

From this point, the Dow surged 15 percent to 987 by the end of October, amid the Yom Kippur War and Vice President Spiro Agnew’s forced resignation. Bulls were lulled into believing that a new leg up had begun.

“It’s time to turn bullish,” said Myron Simons of the brokerage Wooden & Co. The two-month rally left the Dow just 6 percent shy of its record high in January. The NYSE’s advance/decline line, though, was not confirming the advance.

On October 19, oil-producing Arab countries instituted an embargo to influence political events. Oil prices quadrupled over the next six months. Inflation was already spiraling out of control, and the US economy entered a recession in November.

The Dow fell 20 percent in six weeks, to 788 by December. For the full year, Treasury bills earned 8 percent compared to the Dow’s 15 percent loss. Valuations collapsed to a 20-year low.

Source: NPR

The brokerage industry’s 1974 market outlook was full of ambiguity and fuzziness. Barron’s columnist Alan Abelson wrote, “Never have so many said so much to such little purpose.”

No one had any confidence in what the new year will bring. After jumping back above 900 briefly in March, the Dow started to weaken again as impeachment hearings against Nixon began. Inflation and interest rates crept higher, while business profits buckled under the weight of a recession.

In August, Nixon resigned. The Dow began another gut-wrenching decline. “It was like a mudslide,” said Ralph Wanger of the Acorn Fund. “Every day you came in, watched the market go down another percent, and went home.”

The Dow dropped from 797 to 584 over the next two months, for a loss of 27 percent. Investors capitulated in despair. There were no bulls left.

“There’s really no place to hide,” offered Bill Grimsley of Investment Company of America. Articles such as “Dow below 400?” from Forbes and “Is there no bottom?” from Newsweek were typical.

Fortune ran a story titled “A Case for Gloom About Stocks,” suggesting the bear market was not winding down. Less than two years earlier its editors had proclaimed that “the flush of robust prosperity is suffusing the economy.”

The Dow shot up 16 percent from the October low, but then retested it again in December to mark its final bottom. The bear market of 1973—74 was over, 21 months after it began. The 45 percent decline was the worst ever since the Great Depression.

“The Nifty Fifty were taken out and shot one by one,” wrote a Forbes columnist. From their respective highs, Coca-Cola fell 69 percent, Xerox 71 percent, McDonald’s 72 percent, Avon 86 percent, Disney 87 percent and Polaroid 91 percent.

“Courage! We have been here before,” wrote Jim Fullerton, chairman of Capital Group, in a letter to his colleagues. “Bear markets have lasted this long before. Well-managed mutual funds have gone down this much before. And shareholders in those funds and the industry survived and prospered.”

From 1973 to 1977, the Nifty Fifty stocks underperformed the market, with five-year average returns of negative 4.4 percent annually compared to the market’s positive 2.5 percent. The Dow’s January 1973 high would not be surpassed for another nine years, in November of 1982.