Investing in a bull market is hard enough; hearing it trivialized makes it unnecessarily harder.

It’s easy to say we’re in a bubble. But if you say it enough times, as people have over the years, the word loses its meaning. It’s a troubling symptom of our Cassandra culture whereby people make catastrophic predictions on the back of ideologically motivated cognition.

A cursory reading of Charles Kindleberger’s Manias, Panics, and Crashes shows that speculative manias are dramatic but infrequent. In two hundred years, only the Roaring Twenties and the 2000 dot-com bubble match his standard view of bubbles for US stocks.

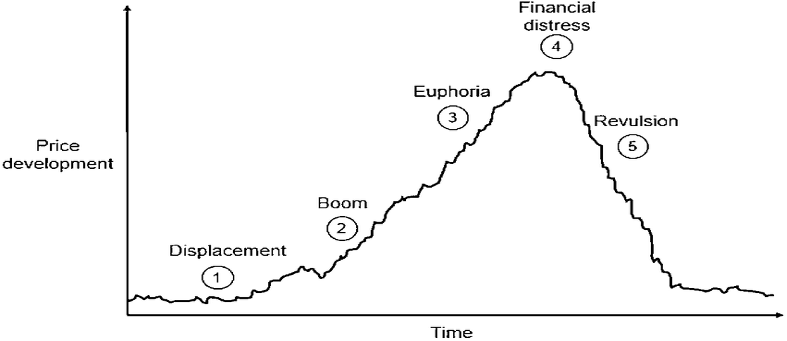

According to Kindleberger, every mania starts with a “displacement,” some exogenous shock that introduces lasting change to the macroeconomy—the end of a war, disruptive technology (canals, railroads, the internet), or an unanticipated change in government policy. The fundamental post-displacement outlook improves in at least one important sector of the economy.

Displacement in the 1920s comprised the mass adoption of automobiles, the development of highways, electrification of much of the country, and the beginning of radio. The collapse of the Bretton Woods system was a displacement that led to the 1970s gold mania. In the 1990s it was an information-technology revolution leading to the dot-com bubble. China’s entry into the World Trade Organization in 2001 was another displacement, which led to the bubble in commodities.

The displacement changes investment horizons, expectations and behavior—the full extent of which remains unclear at first. But once price movements confirm the dominant narrative, an emotionally driven process takes over until it evolves into a state of euphoria. This takes time.

Source: Kindleberger

We believe that Covid-19 is not just the defining global health and economic crisis of our time. The pandemic is a major displacement. It has reordered society in dramatic fashion and accelerated technological adoption, driving changes in consumer and business behavior that will have long-lasting effects.

Millennials are taking over

Last year, millennials surpassed baby boomers to become the most numerous generation in America. That’s 72 million people between the ages 24 to 39 entering their peak earning years. Bank of America reckons millennials’ earning power will rise by nearly three-quarters between 2015 and 2030 as more start work and others gain seniority.

Millennials entered the workforce during the Great Recession, or in its wake, which hampered their ability to buy a home. They were stuck with large student loans, and some were wary after the housing bust. But for the first-time last year, they accounted for half of all new home loans.

And now the sudden Covid-19 shock has prompted millennials to secure their financial future. They are excited about investing.

This cohort, long viewed as never leaving their parents’ homes, is emerging as a driving force in housing. New home sales broke the one million mark for the first time since 2006 last month, rising 43 percent from last year. First-time home buyers accounted for 35 percent of all transactions.

Millennials could be responsible for at least 15 million home sales in the next decade, according to First American Financial Corp. The supply of existing homes, however, is at an all-time low after shrinking for years. New home construction this year will hold steady at just under 900,000, about the same pace as in 2019.

Home prices are surging as a result. Prices are now up almost 7 percent year-over-year at the national level. Seattle, San Diego, Phoenix, and Boston are seeing 20 percent rises on an annualized basis. Kindleberger points out that bubbles in stocks and in real estate often occur together.

Every mania is associated with a robust economic expansion. We think this is coming. Where go house prices and household wealth, so too go consumption and business spending. Unlike 2008 when households came under severe stress, household savings have grown by more than $1 trillion thanks to government stimulus, pushing household net wealth past its pre-pandemic peak.

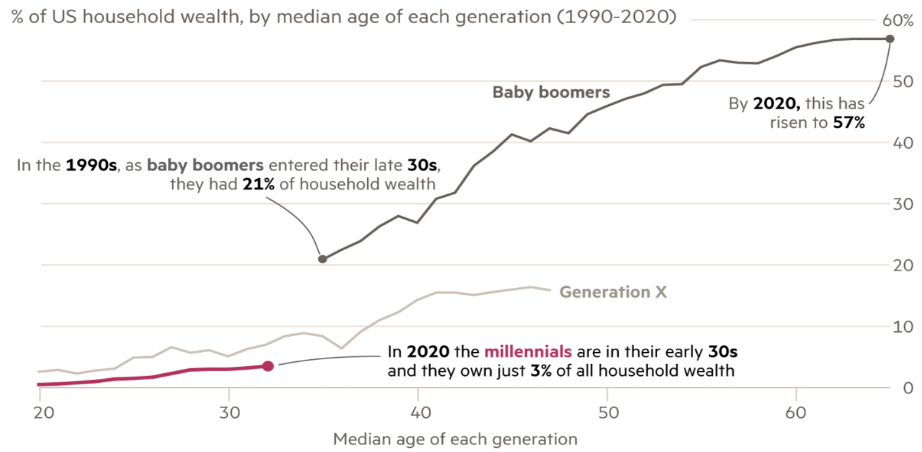

Millennials, owning just 3 percent of all household wealth compared to baby boomers’ 57 percent, have a lot of catching up to do. Their share can rise rapidly as inheritance flows speed up. Every five years $1.3 trillion in investible assets, or 5 percent of the stock, passes down a generation in America.

Source: Financial Times

Prioritizing human outcomes over budget outcomes

America’s response to the coronavirus pandemic revealed something true, says Astra Taylor, co-founder of Debt Collective, a debtors’ union fighting to cancel debts. “So many policies that our elected officials have long told us were impossible and impractical were eminently possible and practical all along.”

Evictions are avoidable; there’s shelter for the homeless in government buildings; water and electricity need not be cut off for late payments; paid sick leave can be statutory for everyone; missing a mortgage payment shouldn’t result in foreclosure; and debtors can be granted relief.

Political action is possible; it needs will. Multi-trillion-dollar programs were mobilized quickly in this emergency, and it will be near-impossible to put that spending genie back in the bottle. Ideas once dismissed as radical are now gaining a hearing. The checks sent to most families in America were a watered-down form of universal basic income.

Income tax was a rare and light burden in the US before 1914, but its adoption grew steadily, first as an emergency measure during World War I and then afterward as governments found that they could tax more heavily without breaking the economy.

Similarly, economic support measures that were temporary in 2020 will expand in the post-pandemic world. The virus is forcing governments to reconsider the social order and prioritize human outcomes over budget outcomes.

The US budget deficit in the fiscal year 2020 tripled to a record $3.1 trillion, or 16.1 percent of GDP. Federal spending will be 224 percent of revenue this year, the highest since 1932.

The costliest economic relief effort in modern history has “proven that no crisis is so deep that a sufficiently large increase in public spending cannot deal with it,” said Warren Mosler, one of the founders of Modern Money Theory (MMT).

MMT has moved from the fringes of finance to actual public policy. There is newfound belief that governments can spend freely without creating inflation. “The power of fiscal policy is really unequaled by anything else,” Fed chair Jerome Powell told lawmakers on a House panel overseeing the response to the pandemic.

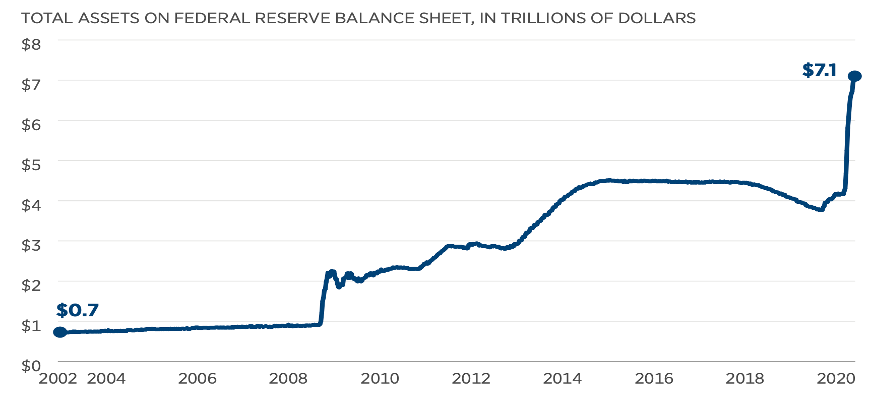

With a balance sheet that stands at $7.2 trillion and Treasury holdings up by a record $2.3 trillion, the Fed owns 20 percent and 37 percent of Treasury notes and bonds, respectively. The Fed is aiding and abetting the government.

Source: FRED

It’s taking longer for employment to recover after each downturn. It took 30 months and 48 months, respectively, to regain jobs after the 1990 and 2001 recessions. It took 76 months after the 2008 crisis. It’s possible that employment levels do not fully recover from the pandemic this decade.

The Fed has abandoned its policy of inflation targeting, widely adopted over the last quarter century, to prioritize employment. And instead of the national unemployment rate, the Fed is promising to consider the job prospects for rate for low- and moderate-income Americans.

The change “reflects our view that a robust job market can be sustained without causing an outbreak of inflation,” said Powell. This pushes both fiscal and monetary policy into a more pro-growth stance, which was never the case in the past decade.

While the world is transforming in ways that are impossible to fully predict, it’s not all doom and gloom. The S&P 500 is at an all-time high without a new stimulus package or the widespread deployment of a vaccine. Far more powerful underlying forces, some outside of common understanding, are at play.

The insight from financial history is that we’ve endured the “displacement” and are only now entering the “boom.” The “mania” phase lies well ahead.

Photo: Shutterstock