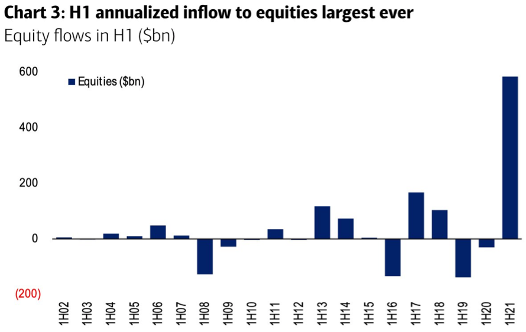

There’s a panic on Wall Street that’s unlike any other: those episodes of sudden widespread fear and credit contraction. It’s a reverse panic, in a way, because investors are buying stocks with unprecedented passion. Previous records of inflows have gone out the window.

Equity inflows are about $580 billion so far this year, following outflows of $246 billion and $187 billion in 2019 and 2020, respectively. If inflows continue at this pace, US equities will take in more money in 2021 than in the previous twenty years combined.

This is a much happier panic. Except for the skeptics and short sellers, everybody gets to feel smart. The retail traders feel like absolute geniuses because of their meme-stock bets. An index that tracks 37 of the most popular meme stocks has doubled halfway into the year. The S&P 500 has only surged 18 percent. Luck is in the air.

Source: Bank of America Merrill Lynch

In a panic state, we are more likely to be irrational. Think back to the overbuying of masks and toilet paper. The same is arguably occurring in the stock market, which is susceptible to emotional contagion. Panic buying is a herd behavior.

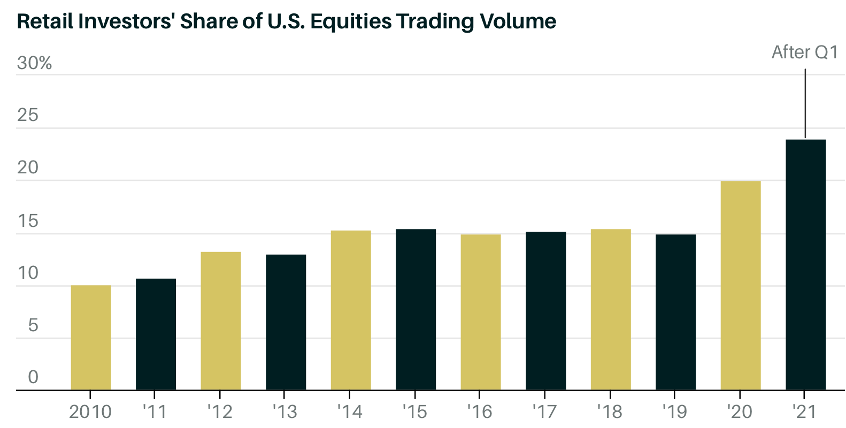

More than $140 billion of so-called “dumb money” has poured into the US stock market in 2021, up 33 percent from the same period a year ago, and six times the amount during the same stretch in 2019. On some days, the retail army accounts for a quarter of all shares traded.

Over ten million new retail brokerage accounts have been opened through June, exceeding the 2020 total. Fidelity is feeding the panic by allowing children as young as thirteen to start trading. The debit balances in margin accounts are now climbing at the highest rate of the past decade.

Source: Bloomberg via Barron's

The real impulse behind the buying panic seldom makes the headlines. It is not a matter of news, but of psychology. In 1935, Lord Keynes wrote:

The social object of skilled investment should be to defeat the dark forces of time and ignorance which envelope our future. The actual, private object is to “beat the gun,” as the Americans so well express it, to outwit the crowd, to pass the bad, or depreciating, half-crown to the other fellow.

This battle of wits is ... so to speak, a game of Snap, of Old Maid, of Musical Chairs—a pastime in which he is victor who says Snap neither too soon nor too late, who passes the Old Maid to his neighbor before the game is over, who secures a chair for himself when the music stops.

It’s not just stocks. We’ve seen the best first half of a year for commodity prices in nearly five decades and the fifth-best for the past century. Yield on the high yield bond index just dipped below 4 percent—for the first time. The highly speculative CCC-rated bonds are yielding 6.5 percent, an all-time low. Credit spreads have never tightened so quickly in the year following a recession.

What about the risks? Après moi, le déluge. Or as Scarlett O’Hara said, “I’ll worry about it tomorrow.”

A bull market lasts years. A buying panic ends sooner. Just as quickly as the symptoms set in, we can feel the sensations gradually subsiding. We’re left with a sense of nervousness and apprehension.

When the panic ends, Keynes tells us, some of the players will find themselves unseated.