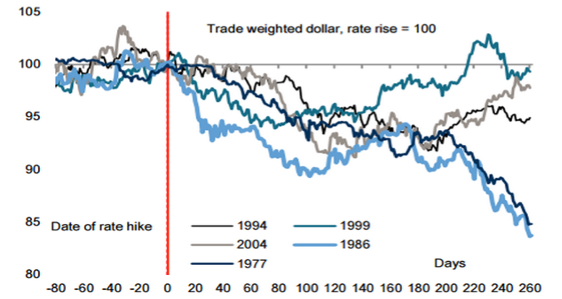

There is nothing predetermined about the way currencies move in response to economic, political, policy, and other external developments. When we look back at previous dollar cycles, we can see that exchange rates can follow many paths that do not always correspond to the predictions from monetary policy actions.

As the Fed raised the funds rate from 4.75 percent in 1977 to 17.5 percent in 1980, the dollar fluctuated in value, but it eventually settled at the same levels. The dollar only began to rally after 1981, when the Fed was already cutting rates as the Latin American debt crisis unfolded.

The Fed hiked rates from 3 percent to 6 percent between January 1994 and February 1995. During this time, the dollar fell 15 percent. It started moving higher after the Fed began cutting rates in response to the Asian crisis and the LTCM blow up.

Between June 2004 and June 2006, the Fed raised rates at seventeen straight meetings, from 1 percent to 5.25 percent. The dollar sank 10 percent, then rose 10 percent, and finished the period flat.

From September 2002 to May 2006, the dollar declined 13 percent, even as the US spread over German bunds increased by 184 basis points, during which time the US budget also swung into a big deficit.

The Fed funds rate remained steady throughout the spectacular dollar rally that began in June 2014 (the largest annual gain since 1985). The dollar remained stable during the hiking cycle from December 2015 to December 2018, when the Fed raised rates more gradually than any other tightening period since the 1950s.

The corollary is that rising US interest rates do not always imply a rising dollar. Since the early 1970s, Fed rate hikes have coincided with the dollar becoming weaker, not stronger.

Source: Credit Suisse

The dollar thrives in the following conditions: (1) falling inflation (and rising real rates) caused by falling oil prices, as seen in the 1980s, 1996-98, and 2014-16, (2) strong US leadership and economic outperformance attracting capital inflows, and (3) global uncertainty and rising risk aversion.

We believe the current macro backdrop has more in common with another dollar bear cycle: inflation is at 30-year highs and the US lacks positive interest rate differentials; the Fed will likely hike rates once-per-quarter, rather than once every six weeks as in the past (this does not strike us as particularly bullish for the dollar); foreign capital inflows are insufficient to cover the US budget deficit (foreign direct investment flows to the US have seen a sharp decline and domestic investors are funding the deficit); and the US is the source of policy uncertainty and risk aversion.

Fed chief Powell dropped the term “transitory” to describe stubbornly high inflation in November and hinted that the Fed could withdraw pandemic support at a faster pace. Despite the hawkish tone, the dollar lost ground, even with a 50-basis points spike in 10-year real yields (although still negative 0.59 percent). The market is telling us something: get out of the dollar.

We’re bullish on the euro. With Germany’s new Chancellor, Olaf Scholz, in charge, and French President Emmanuel Macron likely securing another term in April, the EU can look forward to a more energetic Franco-German leadership.

Macron has called a summit on a post-pandemic economic model for Europe, which promises innovative solutions to the European Union’s long-standing problems, such as greater public investment, a minimum wage in all EU countries, fairer corporate taxation, tougher trade and investment rules, and taking a more proactive role in promoting European champions in key technologies.

Contrast Europe’s political optimism with America’s political gridlock and paralysis. President Biden averaged 49 percent job approval his first year in office (only Donald Trump had a lower first-year average). The midterm elections will shine further light on the degradation of American democracy.

As Seth Klarman warns in his latest investor letter, “An ever-more polarized America, incapable of peacefully bridging our divides, may someday cease to be a reliable destination for investment capital.”

Source: Politico

Over the next two years, the euro area, which is seeing the strongest levels of growth since the single currency was introduced over two decades ago, will outperform the US economy. Employment participation numbers are approaching the pre-pandemic period, unlike in the US which is experiencing an acute labor shortage. The Great Resignation is an American phenomenon that will stifle progress.

The ECB looks increasingly like a “dovish” outlier compared to the Fed’s hawkish monetary policy path. Christine Lagarde, the head of the ECB, stated that she expects the ECB to keep buying bonds throughout this year, and that interest rate hikes are “highly unlikely” before 2023 at the earliest.

Euro area inflation hit a new record high of 5 percent in December. The top-selling German tabloid, Bild Zeitung, warned that “prices are skyrocketing, our purchasing power is melting away,” and put the blame squarely on “Madame Inflation”—a reference to Lagarde.

We believe that inflation in Europe will be stickier than in the US, resulting in a hawkish repricing in favor of the euro. Energy accounts for 7 percent of the total in the US CPI, whereas food accounts for roughly 15 percent. These components have a slightly higher relative weight in the euro area (10 percent for energy and 20 percent for food).

If we are correct in our thinking, it will also prompt the return of a familiar investment theme: the carry trade. Higher inflation has already prompted EM central banks to boost interest rates. In 2021, the central banks of Brazil and Mexico raised rates by 7.25 percent and 1.5 percent, respectively. Now that inflation is starting to cool, their currencies will benefit from a favorable real rate environment.