“What happened?” I ask, arriving at the scene of the fight.

“Zaynab kicked me!” It is my wife, Saniha, laying the accusation. I glance over at my five-year old daughter, who is standing beside her, unrepentant.

“She took my phone without permission and started watching videos. Twice, I asked her politely to give it back, but she completely ignored me. Then, I warned her a third time and snatched it because she didn’t listen.”

Saniha is feeling the side of her belly where it hurt. She looks like Winnie the Pooh at thirty-six weeks pregnant.

“Say sorry to your mother.” I want to diffuse the tension.

Zaynab just stares at me. I look into her big brown eyes to glean if she feels any remorse. “Zaynab!” I insist, an edge of warning in my voice. Her face twists in a frown. She reminds me of how much you can articulate without words. As Susan Sontag said, “Silence remains, inescapably, a form of speech.”

As the minutes pass, I feel myself getting angry. This is not the first time this happens. I grab Zaynab forcefully by the arm and sit her down on the couch. “Is this how we behave? You need to say sorry now.”

As parents, we want our children to take responsibility for their actions, consider others’ feelings, and learn how to make up for their misdeeds. One of our biggest challenges with Zaynab is that she refuses to apologize for anything. It’s like her pride gets in the way. Rather than admit her fault, she deflects blame or acts in ways that are hurtful.

Saniha has been brought to tears several times. Among the things Zaynab has said to her: “You’re just like Cinderella’s wicked stepmother!” “I hate you, get out of my life!” and “I’m going to tell Baba to replace you with a new mother.”

I look disappointingly at Zaynab. She is quiet for what feels like the longest time, her silence causing anxiety in my chest to grow. I start to worry about her future. Novelist Emily Bronte’s words echo in my mind: “Proud people breed sad sorrows for themselves.”

In a flash, I picture Zaynab fighting with her husband, her inability to say sorry putting a strain on their relationship. I remember writer John Ruskin’s advice: “It is better to lose your pride with someone you love rather than to lose that someone you love with your useless pride.”

Pooh Bear mumbles something to herself and walks out of the room. It could be that her tummy is rumbling. Work beckons me, and I leave too, without saying another word.

Zaynab sits there, abandoned.

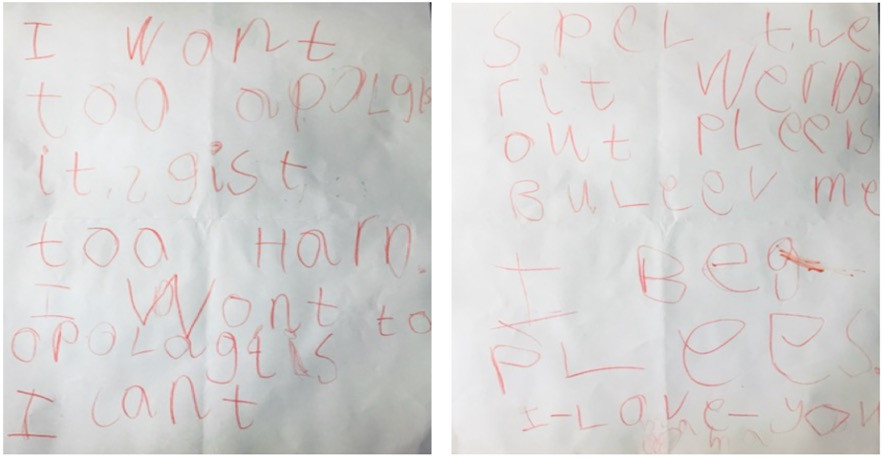

An hour later, Saniha comes into my office with a hand-written note.

My heart sinks. I feel terribly ashamed for what I had done. I misunderstood Zaynab’s silence to mean she is not remorseful, when, in fact, she feels bad about her actions and knows that she is in the wrong. She was just caught in a storm inside her.

What I realize in that moment is Zaynab has trouble separating her actions from her character. If she does something bad, her mind makes her think she must be a bad person, which of course she is not. That is why admitting wrongdoing is difficult. Refusing to apologize was her trying to protect her fragile sense of self. Her pride serves as a defense mechanism.

What matters in how children turn out is how we turn out as parents. Rather than helping her communicate her genuine expressions, my actions were causing her to feel more humiliation. My eyes tear up.

As I walk back into the house, Zaynab stops playing with her toys and runs to me excitedly. I kneel down to receive her as she rushes into my arms with greater force than ever before. I regain my balance and squeeze her tightly.

“Baba, I wrote a letter and gave it to Mama, and we are now friends again. I said sorry and hugged her and…” Zaynab speaks in bursts of bubbly energy, a beautiful smile stretching across her face. She has completely forgotten my harsh treatment.

“Zaynab,” I interrupt. “Will you forgive me?”

Photo: Unsplash